Our Project at the Knowledge City Berlin 2021 Exhibition

The history of plague masks in East Asia / A conversation between Christos Lynteris, Tomohisa Sumida, and Meng Zhang

One mask fits all? Gender and care work in the Covid crisis / by Marianna Szczygielska

Masking our uncertainties: The way of the masks / by Rita Brara

Exquisite masking. A collaborative art project / by Regina Maria Möller and Dinu Bodiciu

Living with masks: dealing with mask-induced pain in South Korea / by Jaehwan Hyun

Don’t ask why Asians wear masks — ask why Western folks don’t / by Mitsutoshi Horii

Mask incarceration: The nexus of pandemic, environmental degradation, and carcerality / by Ariel Ludwig, Jessica Brabble, and E. Thomas Ewing

We can keep silent, but that doesnt mean we dont care / Interview with artist Tran Tuan

Masking the senses: our sensorial world through the layers of the mask / by Noa Hegesh

Thinly-masked: What the Japanese can tell us about facing uncertainty / by Jadie Iijima

The material lives of masks in Japan and South Korea / A conversation between Jaehwan Hyun and Tomohisa Sumida

The transformation. A short history of masks / by Jan Henning

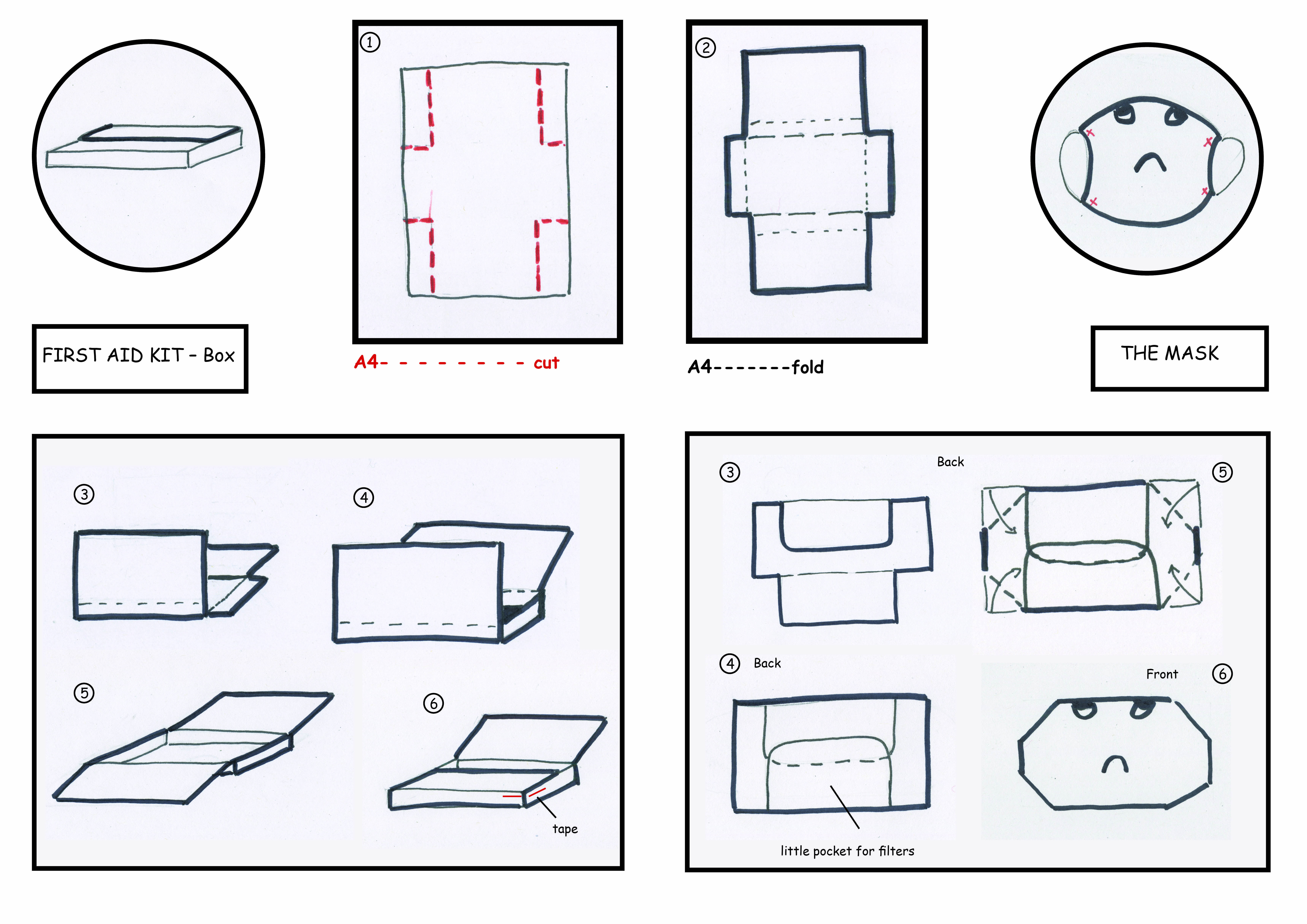

The Mask-First Aid Kit / by Regina Maria Möller

Our Project at the Knowledge City Berlin 2021 Exhibition

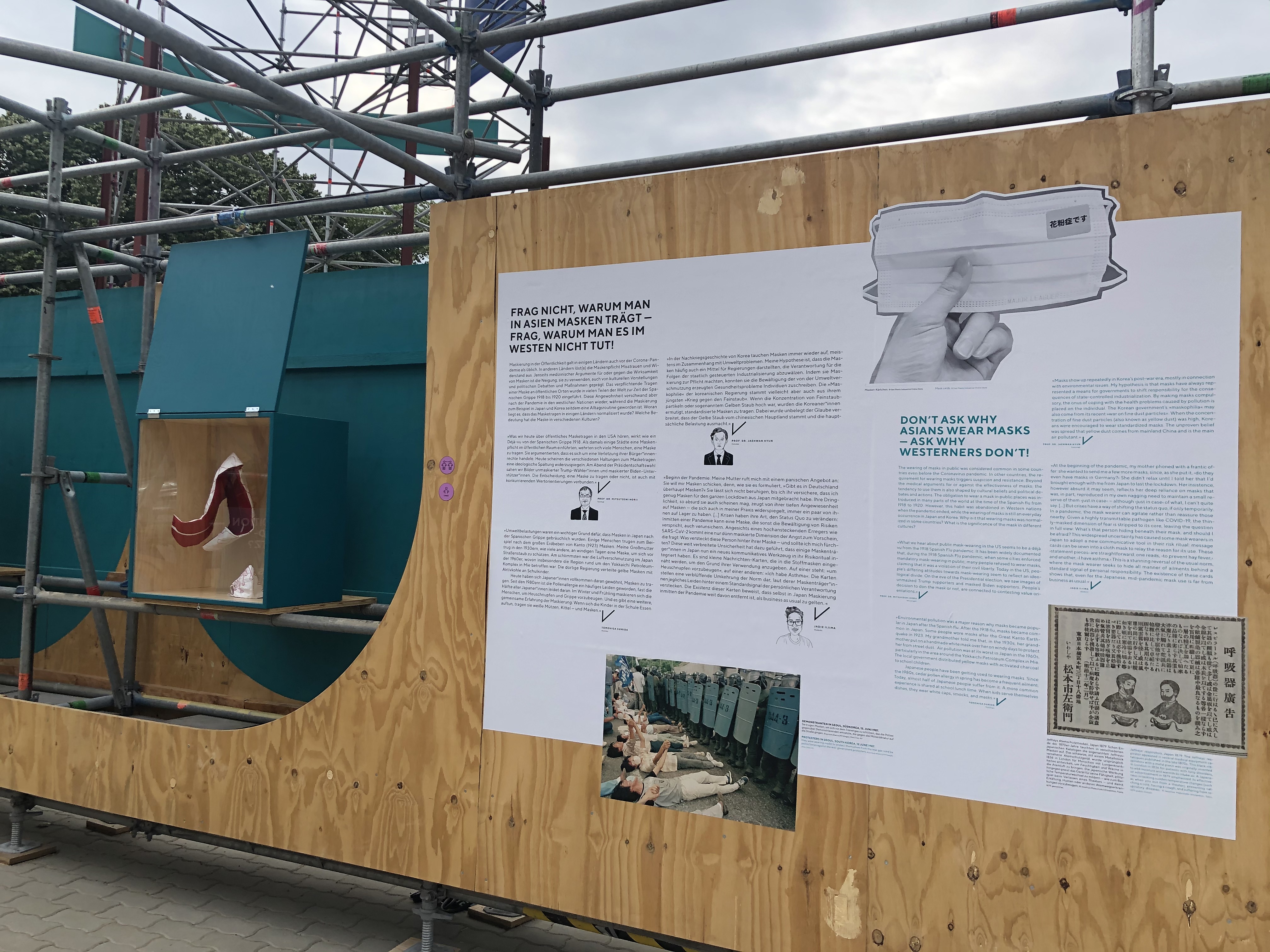

The Mask-Arrayed was part of the “Knowledge City Berlin 2021” programme that focused on the role of science in our daily lives. Our project was featured in a special exhibition on the topics of health, climate change, and social cohesion in times of the Covid-19 pandemic. Visitors could explore this open-air exhibition in front of the Red City Hall in Berlin between June 25th and August 22nd, 2021.

Exhibition view, taken at the opening event. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

The Mask-Arrayed team worked with designers to showcase the history and materiality of the most ubiquitous artifact of our everyday lives during the Covid-19 pandemic. Our collective contribution unmasked the complexity of this seemingly simple object and unveiled its many layers and different usages in both material and non-material terms. We encouraged visitors to observe new knowledge, technologies, and materials in the making, follow processes of adaption and invention, and ask how claims of knowledge and technological functionalities are constructed and defended.

Exhibition view, taken at the opening event. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

Exhibition object by Regina Maria Möller as part of the “Exquisite Masking” series. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

Exhibition view, taken at the opening event. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

Exhibition view, taken at the opening event. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

Exhibition view, taken at the opening event. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

Exhibition object by Dinu Bodiciu as part of the “Exquisite Masking” series. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

Exhibition view, taken at the opening event. Photo credit: R.M. Mueller 2021.

The history of plague masks in East Asia / A conversation between Christos Lynteris, Tomohisa Sumida, and Meng Zhang

As masks began attracting increased attention in 2020, historians of science and anthropologists began independently investigating the situated histories of this iconic artifact. Christos Lynteris’ work on plague masks has inspired Tomohisa Sumida and Meng Zhang to trace the history of masks in Japan and China, respectively. In a conversation between these three scholars, they discuss their research on the history of plague masks in East Asia.

Finding the First Plague Mask

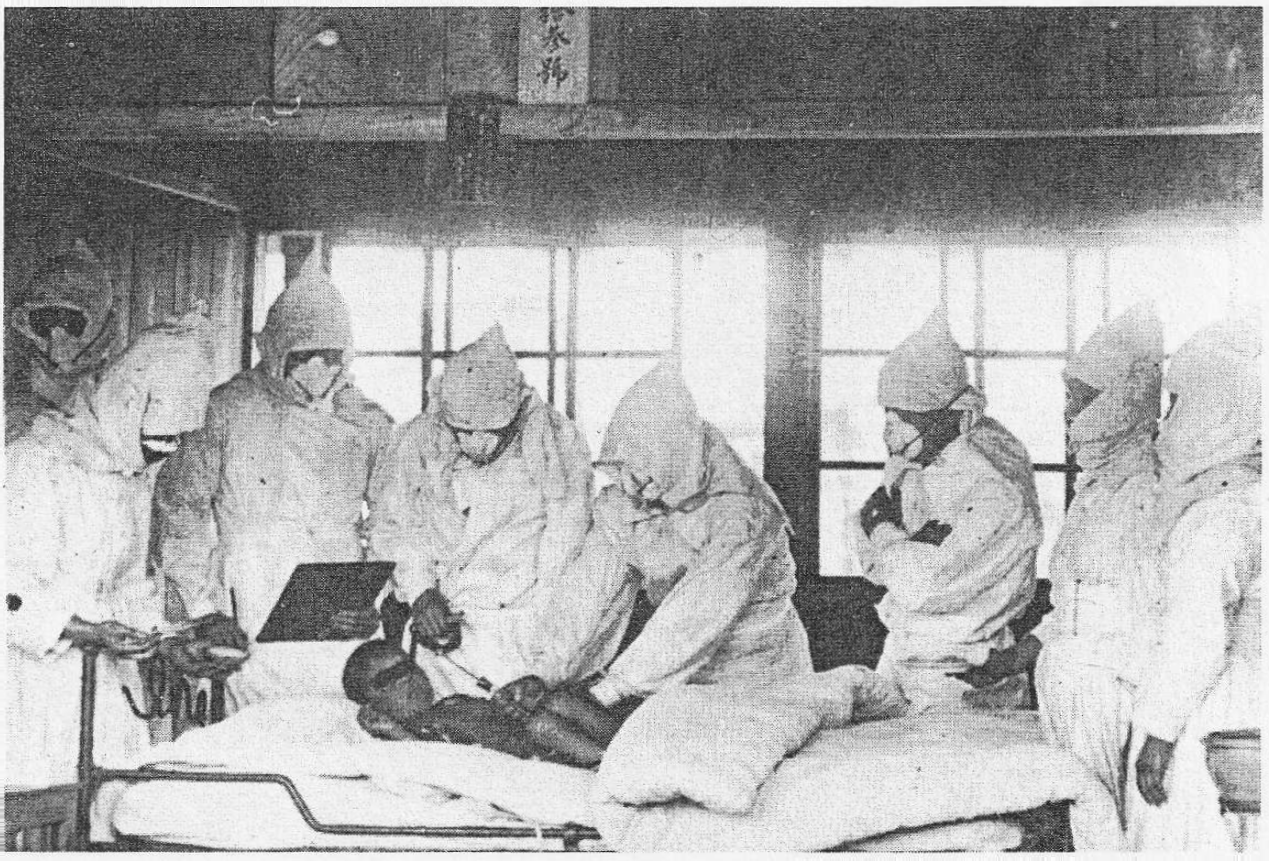

Tomo: When I first started writing on the history of masks for the Japanese journal Gendai Shisō [Contemporary Thought], I read several articles by Christos. In his latest article, published by the New York Times in February 2020, he wrote: “[a]nti-epidemic masks as we know them today were invented in China more than a century ago, during the Chinese state’s first effort to contain an epidemic by biomedical means.”1 So, I wrote in Gendai Shisō, “the use of masks by medical personnel for the purpose of disease prevention began with the Manchurian plague in 1910–1912.”2 After its publication, several Chinese scholars, including Meng, made me realize that I was mistaken. Wu Liande, a Cambridge-educated doctor and the inventor of the so-called “Wu’s mask” during the Manchurian plague, himself mentioned masks that preceded his, in places such as Germany and Japan.3 Christos’ research article in Medical Anthropology had been more carefully written.4 In Japan, doctors and quarantine officers had already begun to wear masks during the plague epidemic in Osaka in 1899–1900, especially after two doctors and one quarantine officer died from the pneumonic plague in January 1900 (Figure 1).5 Christos, do you know of any other cases of early plague masks?

Figure 1. Plague Outbreak, Momoyama Hospital, Osaka, Japan, c. 1900. (Ōsakashiritsu Momoyama Byōin 1987: 222.)

Christos: This is a difficult question, as it depends on what we mean by “plague masks.” The image that comes to mind immediately is that of the “Beaked Doctor.” These early modern physicians wore masks when examining plague patients, which were meant to protect them from miasma. We know from oil paintings that people burying plague corpses in Marseille in 1721 wore cloths around their mouth and nose. Similarly, following the Vetlianka plague epidemic in Russia in the late 1870s, doctors published designs of hazmat-like anti-plague uniforms involving complex respirators. But all these cases were meant to protect doctors from a plague imagined as miasma, or “bad air.” What we see, by contrast, in the course of the third pandemic, already by 1900, is the use of face-covering devices against bacteria. So there is a material continuity in place on the one hand, and an ontological, symbolic and epistemic discontinuity on the other, making it crucial to study their interplay and its material, aesthetic, social and behavioral impact on the ground. What is important is not so much to locate the first “mask” used against disease, but rather to discuss how ideas, practices, and imaginations of face-covering devices emerged in different social and epistemic contexts. This can lead us to think about the ways they started to materialize as “masks” in the strict sense of the term.

Depicting Vernacular Masks

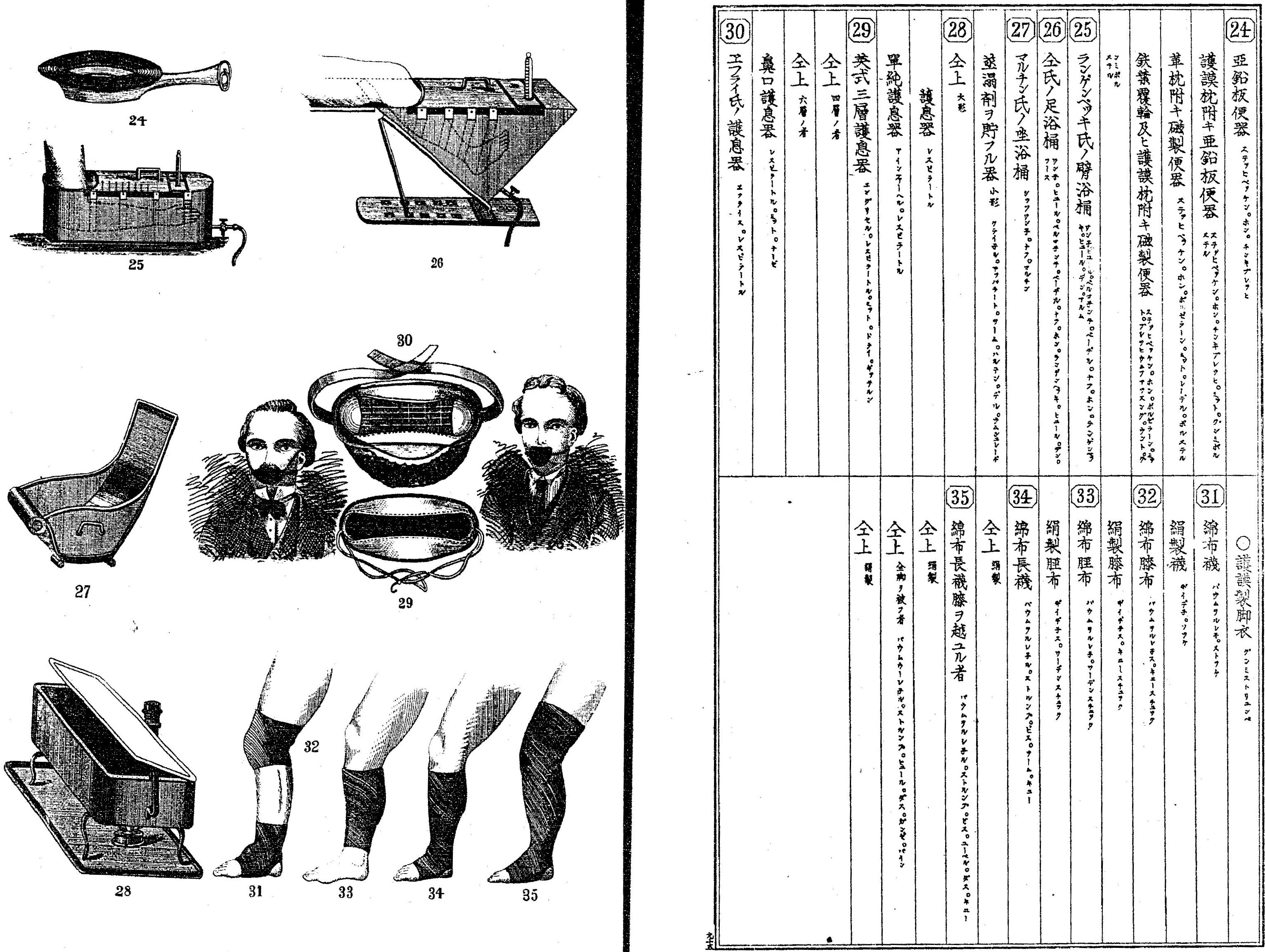

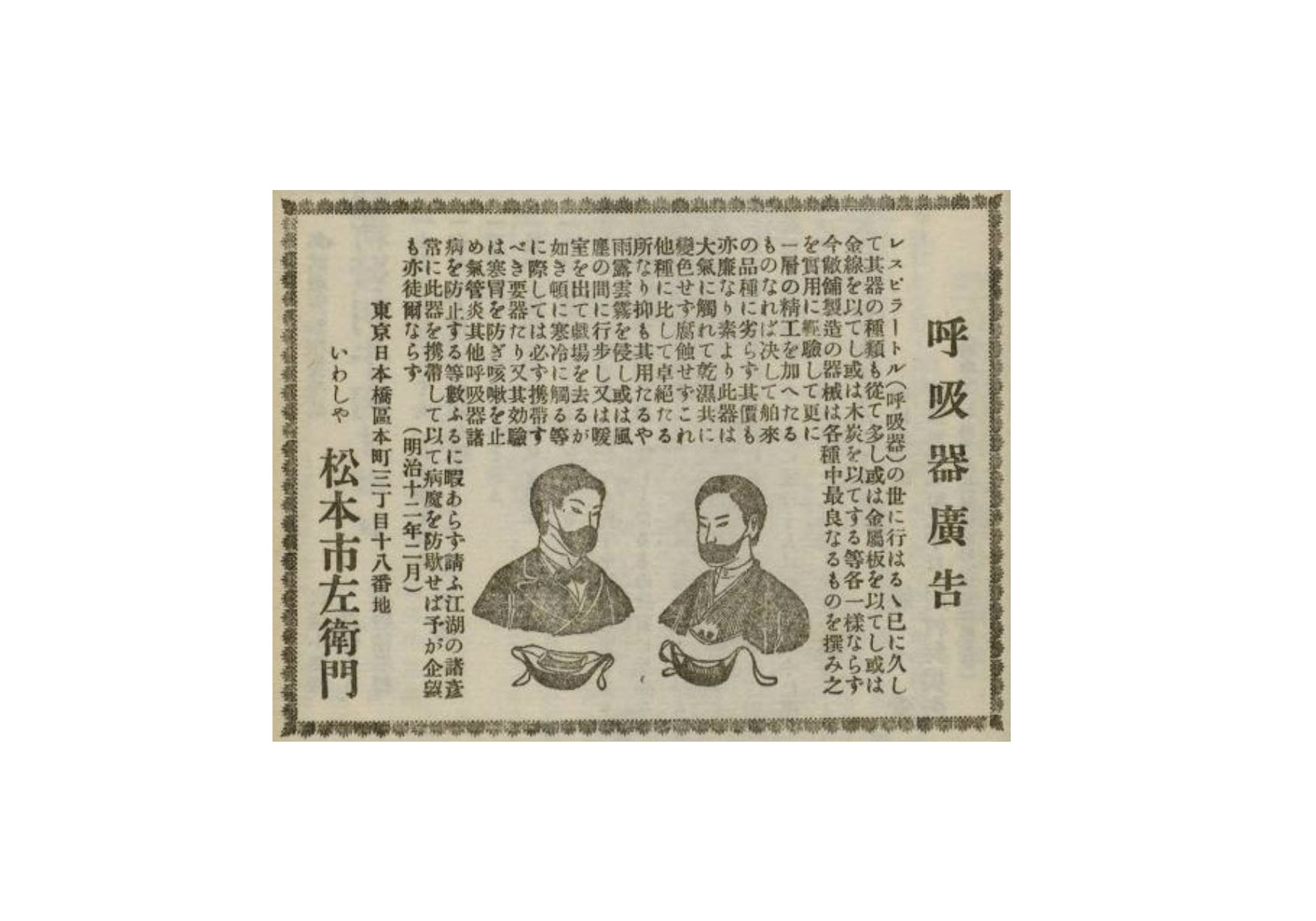

Tomo: In Japan, the “Jeffreys’ respirators” which had been invented in London in 1836 were popular among urbanites in Tokyo at least in the 1870s and succeeding decades (Figure 2). I suspect that people accepted masks as the tools of modernization and Westernization. How can we further understand such folk usage of masks?

Figure 2. Respirators in Meiji Japan. (Top: Matsumoto Ichizaemon eds., Iryōkikai Zufu, 1878, pp. 95–96; Bottom: Marumaru Chimbun, April 26, 1879, p. 1863.)

Meng: Although there is no direct evidence of the common use of respirators in China in the nineteenth century, quite a few English-Chinese dictionaries compiled by medical missionaries from the 1860s clearly introduced respirators to Chinese learners by translating them as huxiqi (literally: breathing apparatus).6 It can thus be assumed that respirators were introduced in some missionary hospitals in China, just like in England and America. In this Chinese context, before 1911 respirators were mainly used for medical purposes. It was in the Manchurian Plague that respirators were massively worn by both medical professionals and civilians.

Christos: We know that then, just as now, people adopted epidemic control technologies by adapting devices to their own cultural and epistemic contexts and political agendas. In reality, all uses of anti-epidemic masks, back in 1910 and today, involve degrees of vernacular reappropriation, signification, and valorization. PPEs are not simply material items, but also symbolic and performative objects. In many ways, it is their symbolic and performative efficacies that are more important in driving the social use of these devices.

Meng: It needs to be emphasized that there was a long-lasting tension between medical experts and Chinese layman, who were not necessarily fans of masks or other plague-prevention interventions. Given this public conflict around anti-plague measures, Wu Liande and his Western colleagues concluded that, without strong political support, mass-masking would not be possible, especially among less educated populations. Dr. Richard Strong, an American medical scientist working in Manila, had later proven that anti-plague gauze masks were not “bacteria-proof,” thereby justifying the suspicion voiced by Chinese locals that gauze masks could not prevent the deadly disease, even though physicians in China had not cast any doubt on gauze masks for many years.

Wu’s Mask Reconsidered

Tomo: In Japan, there had been “fans of masks” even before the plague. During the Osaka plague in 1899–1900, advertisements for the respirators as “plague prevention” apparatuses appeared in the press before the official recommendation came out. That may be why I have not been able to identify the early promoters of anti-plague masks. So, I would like to ask both of you to comment on the importance of Wu’s intervention.

Christos: What Wu achieved in 1910–11 was not the invention of the anti-plague mask per se, but the transformation of this face-covering device into a global charismatic epidemic control object, one that attracted media attention, and in this way gained symbolic and epistemic value beyond its immediate context and use. Wu’s success, as I have argued, was to transfigure a face-covering device into a mask, in the proper anthropological sense of the term: into a transformative device. This transformation also depended upon rendering this device into a visual object – something achieved through the application of photography on the ground, including self-portraits of Wu. We also need to remember that Wu continued developing and applying the mask to epidemics in China for many years. In the course of the second Manchurian plague epidemic of 1920–21, for example, Wu oversaw the production and distribution of 60,000 masks to the general population.

Meng: Before coming to China in the 1900s, Wu Liande studied the so-called tropical diseases, such as plague and malaria in Britain, Germany, and colonial Malaysia. We can suspect that he was familiar with the most recent developments in bacteriology, including the use of respirators to prevent contagion. At that time, bacteriologists and tropical medicine professionals focused mostly on vaccines and disease treatments. The effectiveness of masks for preventing contagion was evident to them and was treated as an obvious fact of everyday work rather than an innovation. As the medical chief of Harbin, Wu Liande seemed more interested in the etiology of the pneumonic plague rather than its prevention in the form of something as simple as a gauze mask. Moreover, before Wu’s album Views of Harbin (1911) was published at the end of the plague, in April 1911, global media had already extensively reported on the phenomenon of mass mask-wearing in Manchuria (Figure 3). So, we can hardly say Wu Liande had a direct impact on the international perception of anti-plague masks during the Manchurian plague.

Figure 3. The Manchurian Plague in the British news. (“Muffled Against the Deadly Plague-Bacilli,” The Illustrated London News, March 18, 1911, page 1.)

The only recorded experiment on the efficacy of masks during the Manchurian plague was conducted by a Japanese physician who was a student of Kitasato Shibasaburō, known for discovering the plague bacillus. It was not until the early 1920s that Wu Liande started to test gauze masks, probably because he finally realized that the vaccines against the plague, that many renowned medical scientists had worked on for decades, were an unrealistic dream which might never come true.

Christos: Whereas Wu’s album was indeed made available in April 1911, his masks were pictured across international news items on the Manchurian plague epidemic through January, February, and March of 1911. Whereas these did not always attribute the mask to Wu, they became a powerful way to advertise the anti-contagion efficacy of the device and render it into a globally recognizable method of epidemic control. Other masks of Japanese or French design were also represented in these publications as well as in scientific ones, so I agree that it is very important to recognize that the emergence of the anti-plague mask as a global visual object depended not simply on Wu’s efforts, but on an international race for the best mask. The manner in which the international press often paid no attention to realities on the ground and created visual meta-narratives about these devices, which, often by way of comparison to the beaked plague doctor, configured them into icons of medical modernity.

About the authors:

Christos Lynteris is a Senior Lecturer in Social Anthropology at the University of St Andrews. His research focuses on zoonotic diseases, epidemiological epistemology and colonial medicine. The author of four monographs and editor of five edited volumes, he is the PI of the Wellcome-funded project The Global War Against the Rat and the Epistemic Emergence of Zoonosis and was the PI of the ERC-funded project Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic.

Tomohisa Sumida (住田 朋久) graduated from the University of Tokyo with a Master’s degree in the History of Science and is currently working for a Japanese public think tank. His work explores the social dimension of science as it relates to topics such as nature conservation, air pollution, and pollen allergies. In his paper “Covering Only the Nose and Mouth: Towards a History and Anthropology of Masks”, published in the journal Gendai Shisō [Contemporary Thought] in April 2020, the mask is at the center of inquiry.

Meng Zhang (张蒙) earned his PhD in Chinese History from Peking University, China. He is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the School of Health Humanities, Peking University on the research project “Herbal Medicine and Japanese Pharmaceutical Study in Modern China, 1905–45”. He started to look into the history of masks in China and East Asia at the beginning of the Pandemic and published an article titled “From Respirator to Wu’s Mask: The Transition of Personal Protective Equipment in the Manchurian Plague” which examines the knowledge production and circulation of plague masks in 1910/1911 China.

References:

1 Lynteris, Christos. “Why Do People Really Wear Face Masks During an Epidemic?” New York Times, Feb. 13, 2020.

2 Sumida, Tomohisa, “Bikō nomi o ōu mono: masuku no rekishi to jinrui-gaku ni mukete [Covering Only the Nose and Mouth: Towards a History and Anthropology of Masks],” Gendai Shisō [Contemporary Thought], 48, no. 7 (May 2020): 191–199.

3 Wu, Lien-Teh [Wu, Liande]. (1926). A Treatise on Pneumonic Plague. Geneva: League of Nations.

4 Lynteris, Christos, “Plague Masks: The Visual Emergence of Anti-Epidemic Personal Protection Equipment,” Medical Anthropology 37, no. 6 (2018): 442–457.

5 Sumida, Tomohisa, “Western Origins of Japanese Plague Masks: Reflecting on the 1899 German Debates and the Suffering of Patients/Doctors in Japan,” East Asian Science, Technology and Society, forthcoming 2021.

6 Zhang, Meng, “From Respirator to Wu’s Mask: The Transition of Personal Protective Equipment in the Manchurian Plague,” Journal of Modern Chinese History, Vol.14, Iss.2 (2021): 221-239.

One mask fits all? Gender and care work in the Covid crisis / by Marianna Szczygielska

Surgical face masks and filtering respirators are standardized protective gear that accommodate a wide variety of users; they ought to fit any body. Even though these devices were designed as universal and seemingly neutral, they cling to specific bodies differently and signal gendered aspects of care work and vulnerability amidst the COVID-19 outbreak. The embodied gender differences might not be revealed directly in the materiality of the mask itself, but remain deeply coded in the guidelines of use and visual representations of this anti-epidemic technology.

While surgical masks and cloth face-coverings serve as a loose-fitting barrier between the user’s face and the external environment, the N95-type respirators require a very close facial fit to properly seal off the mouth and nose and ensure efficient filtration. As such, properly fitting the respirator might pose a problem for persons with facial hair because it can interfere with its sealing surface. For this reason, in 2017 the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a chart that catalogs various beard and moustache styles according to their suitability for workers who regularly wear tight-fitting respirators.

Image Source: Center for Desease Control

Image Source: Center for Desease Control

While sporting a soul-patch, Zorro or Zappa moustache should be fine, mutton chops, chin curtain, and French fork beard are not recommended. Sometimes the human body needs to adapt to the mask, not the other way around. This humorous infographic contains an important message for ensuring safety of the medical staff, especially given that the latest research on the development of the COVID-19 pandemic shows that men are more vulnerable to infection than women.1

At the same time, women make up 70 percent of the global healthcare workers that are at greatest risk. According to the WHO Health Workforce Department, “women comprise seven out of ten health and social care workers and contribute US$ 3 trillion annually to global health, half in the form of unpaid care work.”2 This means that the vast majority of primary users of medical face masks and respirators are female nurses, residents, and doctors. The current coronavirus pandemic puts their bodies on the frontline. Healthcare workers across the U.S. and Europe are protesting the critical lack of Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) with messages such as: “Don’t send us to battle without weapons! Get me PPE!”. Adopting this kind of military vocabulary that presents the counter-epidemic technology as weaponry against the invisible enemy, echoes the historical context in which some of the first modern respirators were developed, namely, the chemical warfare of the First World War. Even prior to this major stimulus for engineering better respiratory devices to protect soldiers against chlorine, phosgene, and mustard gas in combat, modern respirators were designed for other male-dominated professions, specifically for miners and firefighters, whose working conditions expose them to hazardous dusts, smoke, and carbon monoxide. Just like with most other modern technologies and medical models, their assumed user is a “Reference Man” that is hailed to represent all humanity. In other words, respirators were designed for male bodies in industrial settings and warfare. This stands in stark contrast to care work performed by predominantly female medical personnel battling the coronavirus pandemic at the moment.

But does this history make any difference for contemporary designers and users? Would a respirator modeled on a female body look or function differently? According to a scientific paper on pregnant users of N95 masks, “filtering facepiece respirators developed to meet the respiratory limitations of pregnant wearers might offer a universal design that would improve the comfort and tolerability for all users.”3 Perhaps this perspective and retiring the “Reference Man” could help in designing better equipment for all. Certified facepiece masks are tested for their biocompatibility, or an “ability to be in contact with a living system without producing an adverse effect.”4 This scientific term is typically used to describe the interaction between a biomaterial (for example one used in protheses or implants) and the human body. Even though the face mask is not corporally-integrated in the same way as artificial joints or pacemakers are, it serves as an extension of the body and becomes part of the biological respiratory system. Face masks and respirators come in different sizes but, apart from this variation, their basic form remains the same for differently-gendered bodies. It is the discourse and iconography around the use and availability that is often gendered. Treating a mask as an extension of the body helps to see through different layers of the functionality that this artifact holds for different users.

The performative capacity of the face mask as a lifesaving device can even extend beyond the physical materiality and functionality of the artifact itself. The metonymical face mask is featured in the “Mascarilla-19” campaign launched by the Canary Islands Institute for Equality to combat another global pandemic, that of gender-based violence. This time the mask functions as a code word: asking for a “Mask-19” at a pharmacy allows women who experience abuse or sexual assault to access help. Restricted movement and social distancing rules under lockdown bear gendered consequences, with a reported surge in domestic violence cases. As home is not always a safe space for women, the symbolic mask is being mobilized to save lives. The campaign has started to spread to other Spanish provinces and was also adopted in France. The mask is a powerful symbol: the most desired and inconspicuous object, that quickly became part of everyday life around the globe, helps women who experience violence to voice something that might be difficult to admit and escape.

Image source: Gobierno de Canarias

Image source: Gobierno de Canarias

The idea that faces behind masks are equal can be misleading. In the current COVID-19 crisis, public health experts highlight the importance of keeping track of sex-disaggregated data, but also of gendered behavioral patterns (such as smoking or diet) that can affect immunity.5 Whether it comes to higher fatality rates, design and distribution of lifesaving technologies, or labor regimes of care, gender is one of the key factors that make certain bodies more vulnerable than others during health crises.

About the author: Marianna Szczygielska is Postdoctoral Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin where she works on human-animal relations and materialities. A feminist researcher, she also looks into the gendered aspects of artifacts, technologies, and practices that we encounter in our daily lives.

References:

1 Nanshan Chen et al., “Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 99 Cases of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A Descriptive Study,” The Lancet 395, no. 10223 (February 15, 2020): 507–13.

2 Boniol M, McIsaac M, Xu L, Wuliji T, Diallo K, Campbell J. “Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries.” Working paper 1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 (WHO/HIS/HWF/Gender/WP1/2019.1). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

3 Raymond Joseph Roberge, “Physiological Burden Associated with the Use of Filtering Facepiece Respirators (N95 Masks) during Pregnancy,” Journal of Women’s Health 18, no. 6 (June 1, 2009): 819–26.

4 Michel Vert et al., “Terminology for Biorelated Polymers and Applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012),” Pure and Applied Chemistry 84, no. 2 (January 11, 2012): 381.

5 Clare Wenham, Julia Smith, and Rosemary Morgan, “COVID-19: The Gendered Impacts of the Outbreak,”The Lancet 395, no. 10227 (March 14, 2020): 846–48.

Image credit: Nurse with mask in the Spanish flu ward 1918. Walter Reed. Harris & Ewing photographers / Public domain

Masking our uncertainties: The way of the masks / by Rita Brara

A mask does not exist in isolation; it presupposes other real or potential masks by its side, masks that might have been chosen in its stead and substituted for it.

-Claude Levi-Strauss, The Way of the Masks

An overwhelming sense of uncertainty fogs the Covid-19 pandemic and cityscapes in India as elsewhere in a planetary reminder of our common environment. Our uncertainties are multi-faceted—personal, practical, and social—but resonate in the insistence that we consider science-based inputs and the accompanying masked and unmasked claims regularly (if not 24/7). As people, cognizing claims that are evolving, we come to inhabit and re-inhabit our masking contexts and practices while embodying the realization that there is no masking our inequities.

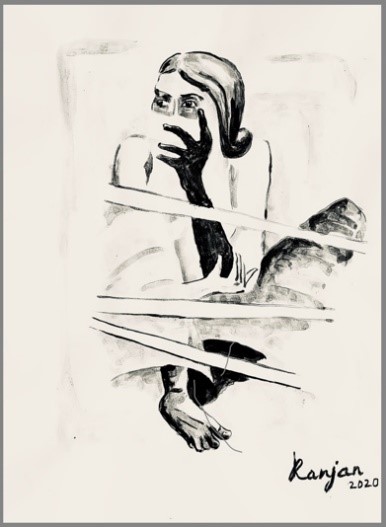

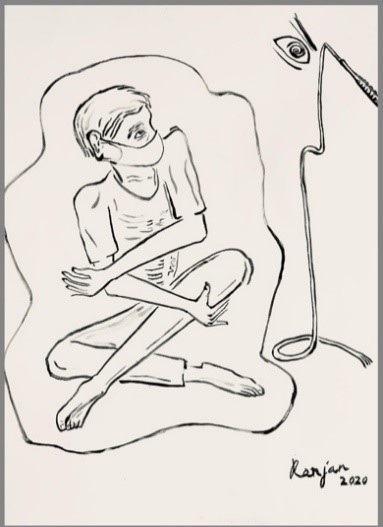

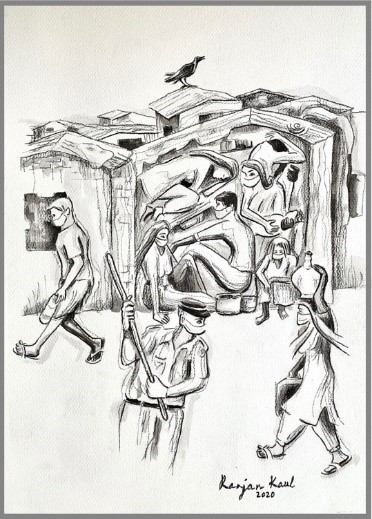

The masked appearance is simultaneously the tell-tale mark of the policed citizen. What lies behind the ubiquitous masking in the city’s underbelly is etched in the accompanying graphic representations. Ranjan Kaul, a Delhi-based artist, portrays the context of slum-dwellers in the city through a panel of charcoal drawings. His first frame focuses on a woman who perceives her hand as unnatural, oversized, and oppressive as it foists a mask that leaves her gagged and bound. The emaciated, masked man in the next frame is immobilized by the state-mandated curfew. The watchful eye and the whip in the corner, ready to be cracked, sums up the ocular display of power outside. The third drawing recreates a condensed image of the slum. People are huddled in a single-room tenement with an ominous crow above. A man is walking back from the slum’s common toilet and a woman is bringing water home (since the area does not have a piped supply). These activities cannot be disallowed, but the image of the policeman brandishing his cane is omnipresent.

“Shut Up” © Ranjan Kaul 2020. Image reproduced with the permission of the artist.

“Whiplash” © Ranjan Kaul 2020. Image reproduced with the permission of the artist.

“Crushed” © Ranjan Kaul 2020. Image reproduced with the permission of the artist.

The artist’s titling accentuates his role as interlocutor, unmasking the perspective of the powerless, but the masking strategies of Delhi’s political honchos and its middle classes also call out for an unveiling.

We see through the masks that our politicians don on mass media in trying to make the nation appear all of a piece, disguising existing inequalities. A mask made of khadi or handloom cloth—fabric symbolic of India’s pre-independence struggle for self-reliance—is the preferred material for making political statements. The charade of such masks is hard to miss—the material is hand-woven cotton, and yet it is a class apart in texture and genre from the loose, coarse cloth that drapes the mouths and noses of the impoverished.

How might one capture the diverse masking moves and strategies of the burgeoning middle classes in the city? Women frequently wear homemade masks or pleat scarfs fashionably and economically while the men, as a class, tend to opt for those that are industrially produced. Washable masks are chosen over the blue-and-white, single-use, disposable surgical masks sold at inflated rates and inhospitable from the angle of environmental recycling and disposal. But without a shred of doubt, no mask is more desirable than the N95 for the middle classes. It is revered as more than a facemask, which presumably filters out 95 percent of suspended air particles. Much before suggestions for reserving it for frontline health workers were articulated, middle-class anxieties had stoked it into becoming the most coveted weapon of self-defense against the virus. It is expensive by average standards, and yet the rush for the N95 gold led it to vanish fairly early from e-commerce sites.

The N95 mask created a flourishing black-market at the chemists. A friend disclosed, “I could get an N95 only after asking a friend, who asked a friend, who asked a doctor, who knew a chemist. Phew!” Another apologetically said, “What mask do I use? I don’t have an N95 but I make do with a black one that I was offered as a substitute.” The N95 has acquired a negative, magical aspect as well. An acquaintance recounted, “I checked with the chemist to make sure that this N95 mask wasn’t from China. Good heavens! I didn’t want anything from there.”

Having managed to procure two or three of the fast-disappearing N95s at exorbitant prices, the betwixt and between people do not rest at that. Figuring out when to wear the N95, for how long, and how to reuse it in an effective, environment-friendly, frugal, and family mode, make up the daily tryst with scientists who said this or that. Most citizens are aware that one-time use of the N95 is considered proper at hospitals. But experimentation is irresistible with the short trip to the grocery store or over that early morning walk. Here the perfect conditions for imperfect figure-it-for-yourself knowledge abound, conjoining science and frugality.

A cousin sanguinely reported that she suns her N-95 mask for thrice the number of hours of use. An acquaintance said, “Ah, the virus dies out after 24 hours max, so I just air it in a clean place for that long.” A friend commented, “Well, at hospitals, the N95 is used for at least four hours at a time. I wash mine in alcohol after 4 hours of use that are spread over four days or so. Hey, but I am not even sure that mine is not a counterfeit N95…just masquerading. I have suspected it all along, but now the papers confirm that the N95s’ branding is something of an uncertified industry.”

At the other extreme, a not-to-be-outsmarted member of the upper-middle stratum proudly declared, “I have an imported N99 mask. I purchased this as an anti-pollution mask from Khan (an upscale market) long before we had a hint of the coronavirus…I wouldn’t buy it now…but it has helped to bring down my anxiety level though you can never be certain. I had purchased three such anti-pollution masks—for my wife, son, and myself—before this corona thing started.” He sent me a picture of the washable N99 mask. It says that it is produced by the “Cambridge Mask Co. England” and “its filters are treated with silver to actively absorb and kill bacteria and viruses.”

Even as the middle strata’s cleaning techniques enact and cloak unknown medical and environmental consequences and risks, the persistent question is how to stretch the N95 and other assorted masks over the uncertain duration of the Covid-19. Caregivers privately express everyday uncertainties about how to keep the uneasiness of masking at bay for the old and the young at home and accompanying transgressions of the scientific temper.

An over-sixty mother was “through with masks that choke” even as her doctor-daughter insisted that masks must be tight-fitting. Another sixtyish mother said that she feared she was “going mental” living alone, and so her son offered to stay with her as he was working from home. As she put it, “Either he or I may be presymptomatic or asymptomatic, but he is flying in to be with me in my tiny flat because… I cannot go on like this much longer…I have cast off my mask.”

A daughter who had not seen her parents over the lockdown period preceded her meeting with a sanitized, brand-new mask. Laughingly she narrated, “Lo and behold! My parents just pulled me towards them and hugged me… their scientific attitude seemed to have evaporated momentarily…” Another youngster conspiratorially declared, “I wear just about any mask to filter out parental worries and as optics for the cops.”

Two of the women I chatted with in my neighorhood had set aside a few homemade masks in their corona-fighting arsenals for a Coro-rainy day. How they came by these masks revealed a story within the story. As the shortage of industrially produced masks exacerbated, it led to a push for homemade masks. In the strike-while-the-iron-is-hot spirit, a few enterprising women here fashioned the mask as an income-generating, ecologically wise stock-in-trade, including designer masks, but did not find sales figures to match. As my young neighbor recounted, without access to thread and couriers through the lockdown, the enterprise could not be strung together for very long. And soon, the produce came to be masked as gifts to friends in the vicinity, sold to neighbors at cost price (to keep tailor salaries going) or offered up as donations.

Perhaps mas(k)querading garbs the uncertainties of our corona times—a mythical dress code in the way of the masks.

About the author:

Rita Brara is affiliated as a sociologist and Senior Research Fellow with the Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi, India. She works on environmental/agrarian law, climate change, gender and kinship, and visual culture. Her most recent research focuses on social constructions of COVID 19, the natural environment and climate change.

This article was first published on Seeing the Woods, a blog by the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society in Munich and is reposted with permission of the RCC and the author.

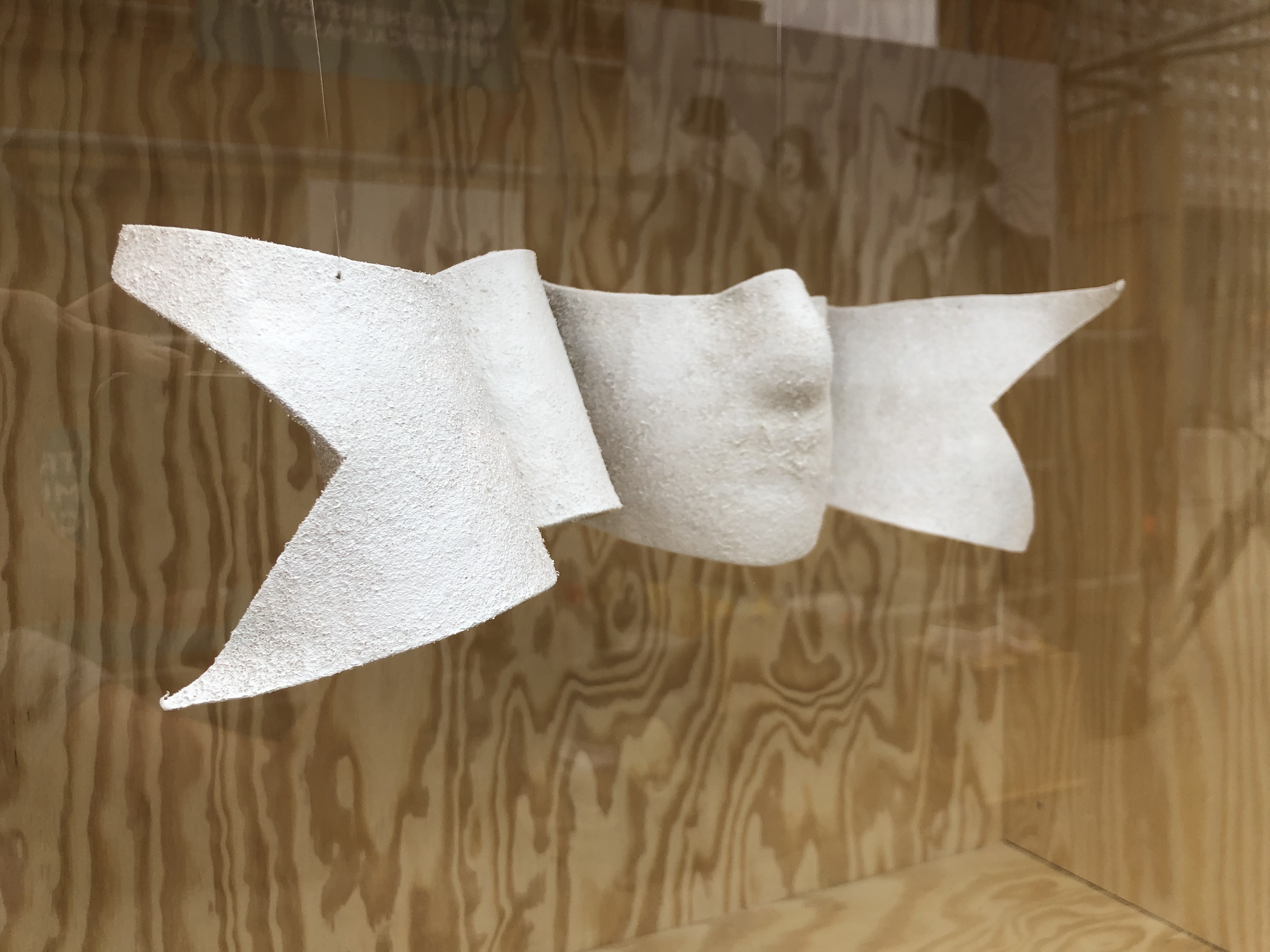

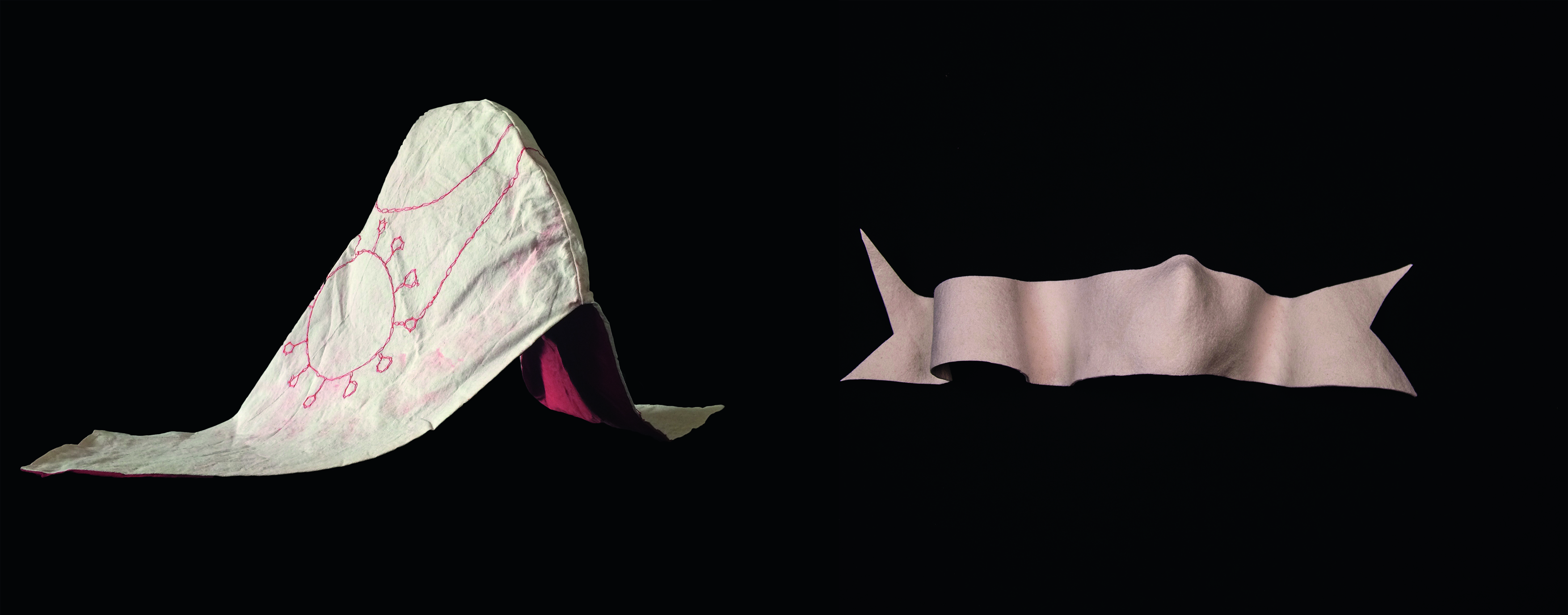

Exquisite masking. A collaborative art project / by Regina Maria Möller and Dinu Bodiciu

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, one item has quickly become prominent around the world – the face mask. While healthcare workers are running short on high-tech protective face devices such as N95 respirators (equivalent to the European FFP2) most citizens are concealing their mouth and nose area with simple face masks made of cloth, or protecting their face by pulling a shawl or turtle neck pullover up to the bridge of their nose. All in all, this little item is changing our public appearance and behaviour. It certainly needs getting used to for many people, while for others it is already common practice to wear face masks on a daily basis, although for different reasons. But from now on this little piece of cloth in front of our face will become our ubiquitous daily companion. The mask itself has many faces—it is an extension of our face, protection, a signal of empathy, an accomplice, a silent speaker, a symbol, camouflage, an incognito masquerade, a loss of identity and bodily senses, a message, a force, a fashionable accessory—Exquisite Masking.

We, Regina Maria Möller, an artist and scholar based in Berlin, and Dinu Bodiciu, a designer and educator living in Singapore, have started brainstorming in a chatroom about transforming a face mask into another useable garment which encompasses and addresses a variety of readings, similar to the mask. The closest item we came about with is headgear, given that both serve a different function around the head. Due to the challenge of the geographical distance between us, we have simultaneously been experimenting with the format of “collaboration”. After exchanging our ideas, we drafted sketch drawings, which we “handed-over” in the digital forum. These drawings were the basis from which we separately extended or intertwined our vision for the object that each of us was about to create. We did not know what the other side was about to construct until we shared our first models. This project development followed a similar journey to the drawing game called “exquisite corpse”, which Surrealist artists frequently used to generate new and unexpected ideas.

When we are talking about communication over digital platforms, whose presence in our lives has intensified in these times of isolation, we should also talk about miscommunication. While developing this project and chatting from opposite parts of the globe, Berlin to Singapore, we discovered how the flat digital images that we have produced as the outcome of this collaboration become alienated. Furthermore, the intended purpose of the pieces we have designed disappears when a receptor perceives these objects as just a bi-dimensional representation.

The alienation of a liminal object—is it a mask or not a mask? is it a hat or not a hat? is it an artefact or not an artefact?—is opening up territory for endless possibilities of interpretation far removed from our original scope. This continuous unfolding of reality in each person’s imagination under the influence of our existing knowledge of material culture might lead to a possible future where we will be all connected, whilst all lost in translation.

The results are two different interpretations of a mask which transforms into headgear—the Exquisite Masking.

© Regina Maria Möller / Dinu Bodiciu: “Exquisite Masking, #6 & #1”, 2020

#2 © Dinu Bodiciu

#3 © Dinu Bodiciu

#4 © Dinu Bodiciu

#5 © Regina Maria Möller, VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

#6 © Regina Maria Möller, VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

#7 © Regina Maria Möller, VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

#8 © Regina Maria Möller, VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

Image credits: Regina Maria Möller / Dinu Bodiciu, „Exquisite Masking“, #1–#8, 2020

#2–#5 created by Dinu Bodiciu, material: felt

#6–#8 created by Regina Maria Möller, material: cotton embroidered and starched

About the artists:

Dinu Bodiciu is a Romanian-born designer, currently living and working in Singapore at the Lasalle College of the Arts, where he leads the BA in Fashion Design and Textiles. Some of his works have been famously worn by Lady Gaga or featured in the “Hunger Games” movie series, episodes 3 and 4. He designs garments and hat accessories that challenge the way we think about the relationship between the human body and clothing.

Regina Maria Möller is a German artist, founder of the magazine “regina” and the art label “embodiment.” Her artistic projects are exhibited worldwide such as the 47th Venice Biennale, Manifesta 1, the 3rd Berlin Biennale of Contemporary Art, Secession, Vienna, NTU Center for Contemporary Art Singapore, among many others. Parallel to her art practice she has given talks at international platforms and taught in a number of academies and universities, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge/Boston; the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim and Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.

Living with masks: dealing with mask-induced pain in South Korea / by Jaehwan Hyun

“I packed my bag and in it I put… a mask, and then a few more, perhaps hand sanitizer…” this is how the popular car game might go in COVID-19 days. When I decided to take a trip to Seoul in mid-May, I packed three different types of face masks: three KF94s, two KF80s, and four surgical masks. A month before my trip, my family from Korea had sent me this assortment to equip me for my masked journey from Berlin Tegel Airport via Heathrow to the South Korean city of Incheon, my final destination. They could dispatch the masks via international shipping, as at that moment the Korean Customs Service was allowing Koreans to send up to eight masks to each family member living outside the country every month.

At the airports, I wore the mask with the highest level of protection, the KF94. (KF94 masks have 94% filtration of a 0.4 micrometer particle and perform similarly to N95 masks. KF80 masks filter about 80% of a 0.6 micrometer particle and offer an equal level of protection to N90 masks). Whilst in the air, I switched to the soft surgical masks. Waiting for my next plane at the airports, I longed to wear the soft surgical masks again, which were now tucked away in my bag, as I could feel the KF94 irritating the skin behind my ears. Dizziness was setting in as breathing became hard. When I finally reached Incheon and boarded the “quarantine bus” which transported me from Incheon Airport to a walk-through COVID-19 testing center near my house, I covered my nose and mouth with a KF80 mask, which allowed for easier breathing but still offered more protection than the surgical masks.

It was the conventional wisdom of wearing this protective gear, widely shared among Korean citizens, that led me to obtain my mask inventory. When it comes to the risk of viral infection, being in flight is much less risky than at an airport, as the air in the cabin is constantly filtered and circulated. The “quarantine bus” is sterilized and transports very few people (in fact, I was one of only three passengers in a bus with forty-seven seats), so the infection risk inside the bus is no higher than that of airports. Irrespective of the endorsement of scientific experts, the general public in Korea is now corroborating the vernacular knowledge of living with masks in their daily lives with scientific information online. My masked journey from Germany to Korea took me not only to a country where conventional wisdom about wearing protective gear is widely shared among its citizens, but also lead me to feel the pain of a mask—an experience that I share with the historical subjects of my research: Korean and Japanese diving women of the late nineteenth century. Unexpectedly, my research had coalesced with current affairs and inspired me to reflect on masks and pain in the context of Korean historical and contemporary experiences.

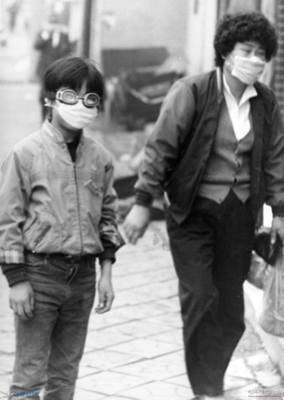

South Korean households are generally prepared to wear masks, but not for reasons of viral threat. American and European observers often describe South Koreans as being part of the mask-wearing culture of the “East.”1 Yet they have only begun to wear these types of masks over the last few years, mainly in order to protect themselves from breathing in micro-dust particles, rather than viruses.2 When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country in January 2020, the Korean public started wearing them as anti-virus masks for the first time. South Koreans have been struggling with the new normal and have started wearing KF94 masks on public transport, in markets, restaurants, and offices since a religious sect called the Shincheonji Church of Jesus became a hotbed of coronavirus in mid-February 2020.3 The South Korean government recommends that people with underlying medical conditions and those making hospital visits should wear KF80 masks, while KF94 masks should be reserved for those in contact with patients who are suspected of having the COVID-19 infection.4 Yet other Korean citizens also wear these types of masks and even prefer KF94s to KF80s because the latter is considered a low-level “yellow dust” mask used against the seasonal phenomenon of dust clouds containing industrial pollutants that come from the deserts of Mongolia and China in the spring.

It is not only the symbolic meaning of KF94/N95 masks that has changed over time, but also the physical conditions. Until last year, Koreans only wore masks outdoors for a limited time. But, to protect themselves against the highly infectious virus, Koreans are now even wearing them during working hours. As a result, more and more people have begun to complain about skin irritation, breathing discomfort, and headaches.

Figure 1. KF94 masks are marketed as the highest-level “yellow dust” masks in South Korea. Photo taken by the author.

As South Korea’s government and media outlets do not consider these mask-induced symptoms a serious issue and instead focus exclusively on stabilizing the supply of masks, citizens are left to find creative solutions to relieve those symptoms by themselves, making various technical improvements at the individual level. A DIY kit to make a breathing valve has become a major success, regardless of its questionable efficacy. Although public health authorities warn against the use of an exhaling valve that might increase the risk of users exhaling viruses, many people prefer this option. A variety of ear strap extenders has already been produced using 3D printers since last February. Traditional medical treatments or pain relief are the immediate solutions to get wearers through the day.

Figure 2. Jeju sea women wearing different types of diving masks in Busan, South Korea in 1952. Courtesy of the Bukyung Modern Historical Materials Research Institute.

A historical episode of mask wearers coping with the pain they induce might provide inspiration for how contemporary Koreans could adjust to face masks. The sea women (海女), called Haenyeo in Korean and Ama in Japanese, are free-diving women who harvest seafood and seaweeds underwater in a traditional way. From the 1880s, Japanese women divers began wearing diving goggles to protect their eyes and enable clearer vision underwater. Soon, they experienced the problems of face squeeze caused by the difference in pressure inside the mask and the ambient pressure of the ocean. To counteract this, in the 1890s, local artisans in the western region of Kyushu attached air-filled compressible rubber bags to their goggles. In other regions, divers devised a face mask with a mouth-straw to boost the air pressure within the goggles. Even before that, a nose-covered version was developed which increased air pressure by nose-breathing.5

Yet, technological modifications did not seem to be the solution that the sea women chose. Although today’s museum exhibitions describe how the nose-covered diving mask soon became the standard type, due to its technological superiority over other designs, a variety of diving goggles co-existed over the decades. This was especially true for the Korean sea women who had migrated to different provinces of Japan as cheap fishery laborers and, as a result, wore various types of diving masks during the period of Japanese colonial rule of Korea (1919-1945). After liberation from Japan in August 1945, Korean divers returned to Jeju Island in South Korea. Some of them wore eye goggles with compressible rubber bags attached, while others used diving masks which covered their noses as well as their eyes. The nose-exposed type continued being used until the early 1960s, when rubber diving masks made in Japan had just begun being introduced to the island. Even young divers wore the simple type of two-eye goggles.6

Instead of technological solutions, it was eventually an agreement within the community that alleviated the divers’ exposure to face squeeze. Regardless of which diving mask the women wore, most of them avoided the severe pain caused by pressure differences by limiting their diving depths as well as the time they spent underwater. In the early 1940s, Gitō Teruoka, the first scientist to study the physiology of the Japanese women divers, thought that modesty was the reason why the women did not endanger their bodies, by balancing their working hours and monitoring their diving depth.7 He did not consider that their restraint was, firstly, a way to manage the physiological risks and, secondly, a result of social circumstances, as the local fishery communities strictly restricted operating places and working hours. Even though the regulations were in place for economic reasons rather than concerns for the diving women’s health, those rules allowed the divers to work sustainably in terms of managing both their pain and resources.8

Current attention to the (temporary) success of South Korea’s fight against COVID-19 highlights the culture of mask-wearing in Korea, but commentators have not yet considered why South Korea became a masked society. South Korea is an “overworked society” in which laborers annually work 300 more hours than the OECD average.9 Although two years ago the government cut maximum working hours, working unpaid overtime until 9 p.m. is still common. Korean companies also discourage remote work and even force workers to wear the painful masks in the office for long hours. As a 24/7 society, many workers at convenience stores, drug stores, cafés, restaurants, bars, theaters, and delivery centers are expected to work through day and night wearing masks. In this respect, the social agreement to change the long working hours culture is an effective way to relieve the mask-induced pains of Koreans. As the case of the diving women shows, social agreement at the community level is needed to help individuals adjust to the new ubiquity of mask-wearing in a sustainable way.

About the author: Jaehwan Hyun is a historian whose work explores transnational connections of scientists from Japan, South Korea, and the US as well as the role of materiality in shaping such exchanges. One of his projects investigates how the materiality of diving masks and other equipment shaped trans-pacific science and the lives of the sea women after World War II. Jaehwan believes that narrating the living experience of the diving-mask users will help us seek a way to live with masks “wisely” in the corona pandemic. Now he is making an effort to create a research collective in studying the making of “masked societies” in East Asia with other East Asian historians of science and scholars of science and technology studies (STS).

References:

1 Tessa Wong, “Coronavirus: Why Some Countries Wear Face Masks and Others Don’t,” BBC News, March 31, 2020.

2 For a criticism of the use of “yellow dust” masks, see Jae-Yeon Jang, Konggi p’anŭn sahoee pandaehanda [Against the Society Capitalizing Air Pollution] (Paju: Dongasia Books, 2019). As a previous colony of the Japanese empire, in South Korea cloth masks have also been used to guard against the flu in winter, but not as widely as in much of today’s Japan.

3 The cult’s full name is the Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony. See “Coronavirus: South Korea Sect Identified as Hotbed,” BBC News, February 20, 2020.

4 From late May, there has been a new demand for KF80 masks for the upcoming hot and humid summer. See the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “The Use of Masks Recommendation Revision,” March 3, 2020, accessed April 22, 2020.

5 Satoru Tanabe, Ama [*The Sea Women]* (Tokyo: Hosei University Press, 1993), 190–99.

6 According to local artisan Jong Soo Koh, interviewed by the author in Seogwipo, Jeju Island, South Korea, January 8, 2020.

7 Gitō Teruoka, Sangyō to ningen: Rōdō kagaku no kaiko to tenbō [Industry and Humanity: Retrospect and Prospect of Labor Science] (Tokyo: Risōsha, 1940).

8 For the Japanese government’s early regulations of diving fisheries in relation to resource management, see Kjell David Ericson, Nature’s Helper: Mikimoto Kōkichi and the Place of Cultivation in the Twentieth Century’s Pearl Empires (PhD Dissertation of Princeton University, 2015).

9 “Remarks by President Moon Jae-in at a Meeting with Presidential Senior Secretaries to Discuss New Working Hour Regulations,” The Office of the President, Republic of Korea, July 2, 2018.

Don’t ask why Asians wear masks — ask why Western folks don’t / by Mitsutoshi Horii

I started studying the practice of public mask-wearing more than a decade ago. My interest in this specific practice was triggered by the 2009 ‘swine flu’ (H1N1) pandemic. I am originally from Japan, but I have lived in the UK since 1996. During the 2009 pandemic, I saw a number of media images of Japanese people wearing masks in public, and found that it was an interesting contrast to the lack of any such habit in the United Kingdom.

Figure 1: Swine flu leaflet, United Kingdom, 2009. Copies of this leaflet were delivered to all UK households as part of the UK government’s public health awareness campaign that began in May 2009. Maker: National Health Service. Source: Science Museum, London

At that time, my research question was: ‘Why do Japanese people wear masks?’ and I studied the history of mask-wearing in Japan. In 2011 I also carried out a small-scale survey in Japan, asking people in the streets of Tokyo why they wear masks. The fruits of this research were two academic articles in English and one monograph in Japanese.1 In those works, I pointed out that the popularisation of public mask-wearing preceded the scientific evidence of its effectiveness, and conceptualised it as a form of ‘risk ritual’ which functions to restore wearers’ psychological stability by providing them with a sense of control in a seemingly uncontrollable circumstance.

The outbreak of Covid-19 has forced me to renew my interest in the practice of public mask-wearing. My publications on masks were picked up by journalists, and I have been interviewed in a number of media since the beginning of 2020. Journalists usually ask me this question: ‘Why do people in East Asia wear masks?’ and ask for my view on the cultural aspect of mask-wearing.

In recent months, I have been wondering whether we have all been asking the right question. When we ask why people in East Asia wear masks, we are gazing at East Asia from the West, where public mask-wearing is not the norm. I have realised that this Western curiosity towards East Asian public face covering was tacitly authorising the Western cultural norm of face exposure in public as the universal standard of public civility.

Since this realisation, I have been asking a different question: ‘Why don’t people in the West wear masks?’ I have found this a more interesting question, one which could challenge the cultural hegemony of Euro-American modernity.

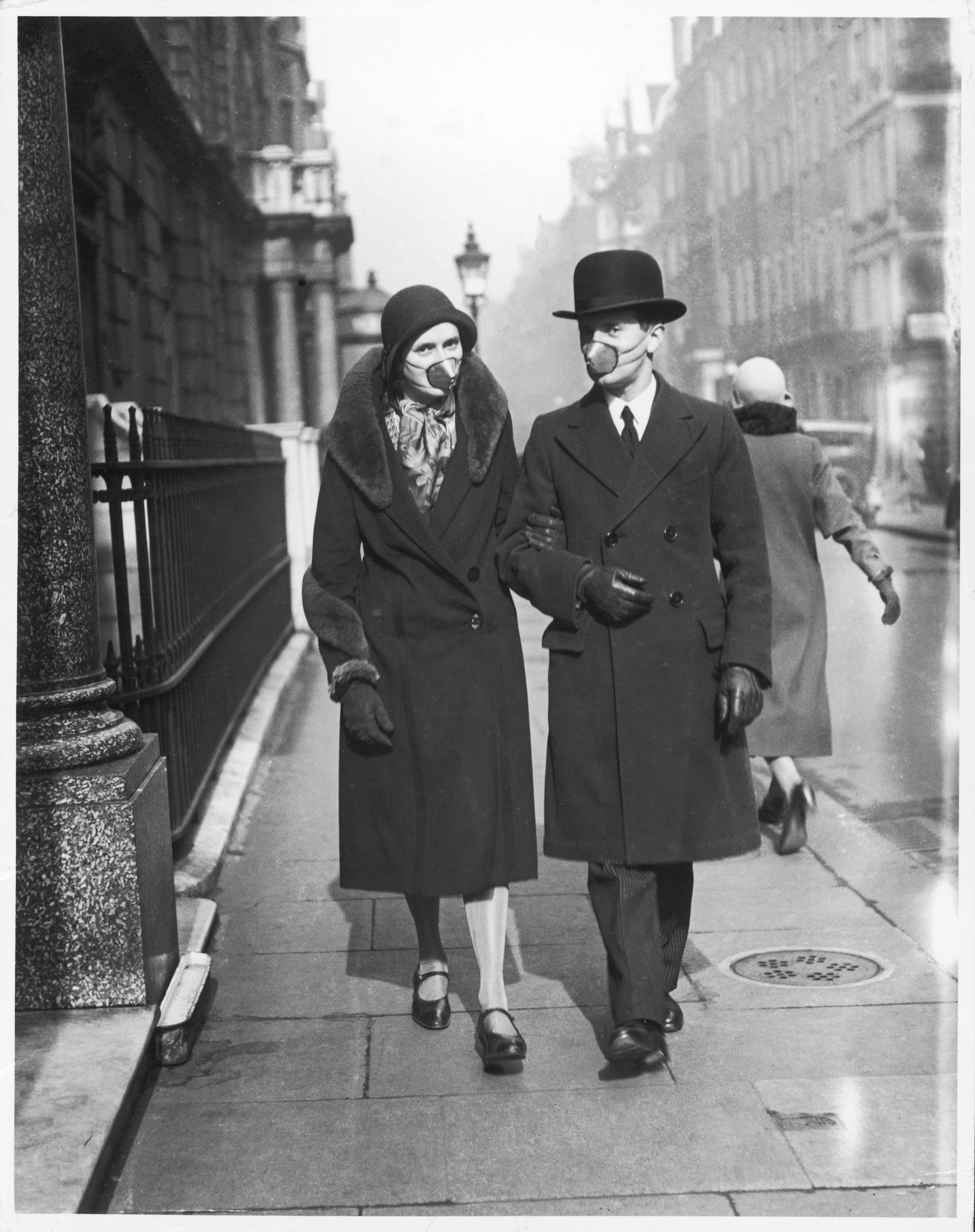

Mandatory mask wearing in public spaces was first introduced in Western nations as a public health policy during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. This was also the case in Japan at the time, and since then wearing a mask in public has been incorporated into Japanese people’s daily routine. In contrast, this practice mysteriously disappeared in the West after the pandemic. Why? This is an interesting historical question, for which I do not have any answer.

Figure 2: Another bout of flu that killed so many in Britain after WW1 lasted from 1929 to 1937. People wore surgical masks or stylish nose caps as this couple demonstrates. Source: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Now, a century later, mask-wearing in public has been re-introduced in the West as a result of the Covid-19 outbreak. Living in the UK, I have been watching this development with great interest. I would like to offer three observations that shed light on some factors connected to mask-wearing in the West.

- ‘Science’ as a human activity: The effectiveness of mask-wearing as a public health measure against infection was not initially recognised by Western governments and the WHO, partly due to the lack of scientific evidence. During the first wave of Covid-19, however, it became more apparent that there were actually lots of scientists who endorsed mask-wearing in public. Many Western governments and the WHO eventually changed their policies on mask-wearing. This issue reminds us of the fact that ‘science’ is a human activity which involves disagreements, negotiations, decision-making, and changing conclusions.

- Face-coverings and civil liberty: What we hear about public mask-wearing in the US seems to be a déjà vu from the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. It has been widely documented that, during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, when some cities enforced mandatory mask-wearing in public, many people refused to wear masks, claiming that it was a violation of their civil liberty. Today in the US, people’s differing attitudes towards mask-wearing seem to reflect an ideological divide. On the eve of the Presidential election, we saw images of unmasked Trump supporters and masked Biden supporters. People’s decision to don the mask or not, are connected to contesting value orientations.

- Two sides of the mask: When Donald Trump tested positive for Covid-19, Speaker Nancy Pelosi criticised the President for having attended crowded fundraisers and campaign rallies while not wearing a mask: “going into crowds unmasked was a brazen invitation for this to happen”.2 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that “cloth face coverings help prevent people who have COVID-19 from spreading the virus to others.”3 In this light, Trump could be criticised for putting others at risk by not wearing a mask. Pelosi’s remark was interesting because she seemed to think that if Trump had worn a mask, he could have protected himself from the virus. This demonstrates the double meaning of mask-wearing caused by a psychological effect of face covering. From the initial stage of the Covid-19 outbreak, the East Asian practices of public mask-wearing seemed to be driven by individuals’ desire to protect themselves, rather than others. This was widely regarded as unscientific by public health authorities and governments all over the world. When public mask-wearing was introduced in Western nations by spring 2020, people were told to do so to protect others, in case they were asymptomatic carriers of the virus. As soon as one starts wearing them, however, masks give one a sense of protection and safety. More people seem to have started wearing them to protect themselves, rather than others around them. This curious psychological effect of masks, and the transformation in the purpose of their use, needs more critical attention.

Finally, we are left with another question: Will public mask-wearing continue in a post-Covid Western world? The longer the pandemic continues, the more likely it is to become part of Western social norms. However, only time will tell us the answer to this question.

About the Author: Mitsutoshi Horii is Professor at Shumei University in Japan, working at Shumei’s overseas campus in the UK, Chaucer College in Canterbury. His specialisms range from the sociology of risk and uncertainty to the critical examination of the modern Euro-American generic categories in social scientific research. His most recent academic publications include the monograph The Category of ‘Religion’ in Contemporary Japan: Shūkyō and Temple Buddhism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). He is currently writing his forthcoming monograph, The Ideas of Religion and Secularity in Social Theory: A Postcolonial Reflection on Sociology.

References:

1 Burgess, Adam, and Mitsutoshi Horii. “Risk, ritual and health responsibilisation: Japan’s ‘safety blanket’ of surgical face mask‐wearing”. Sociology of Health & Illness 34.8 (2012): 1184-1198.

Horii, Mitsutoshi. “Why Do the Japanese Wear Masks?” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies (2014).

Horii, Mitsutoshi. Masuku to Nihonjin [Masks and the Japanese]. Tokyo: SHI (2012).

3 https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0714-americans-to-wear-masks.html

Mask incarceration: The nexus of pandemic, environmental degradation, and carcerality / by Ariel Ludwig, Jessica Brabble, and E. Thomas Ewing

When the COVID-19 pandemic begins, I am in the process of writing about my ethnographic fieldwork in the New York City jails on Rikers Island.1 Beyond having the highest incarceration rate in the world, Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately arrested and incarcerated in the United States.2 It was out of an impulse to better understand and resist racialized mass incarceration that I chose to return to the New York City jails where approximately 9 out of 10 incarcerated people and corrections officers are Black and/or Hispanic.3

Rikers is a human-made island formed of garbage, farm animal remains, and rat carcasses. It served as the city’s dump (1884-1939), a rancid heap in the East River that was the site of waves of infamous rat infestations.4 Its origins matter. They matter both in terms of the vents that spew rancid steam from decaying filth, but also because of the heft of their imaginary. For instance, one officer standing by the desk near the medical intake pens explains to me: “We will never get respect. We are garbage men for human garbage.” He says this with a resigned tone, the decades having worn away any altruism.

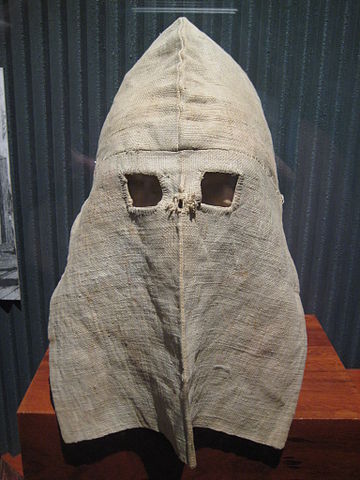

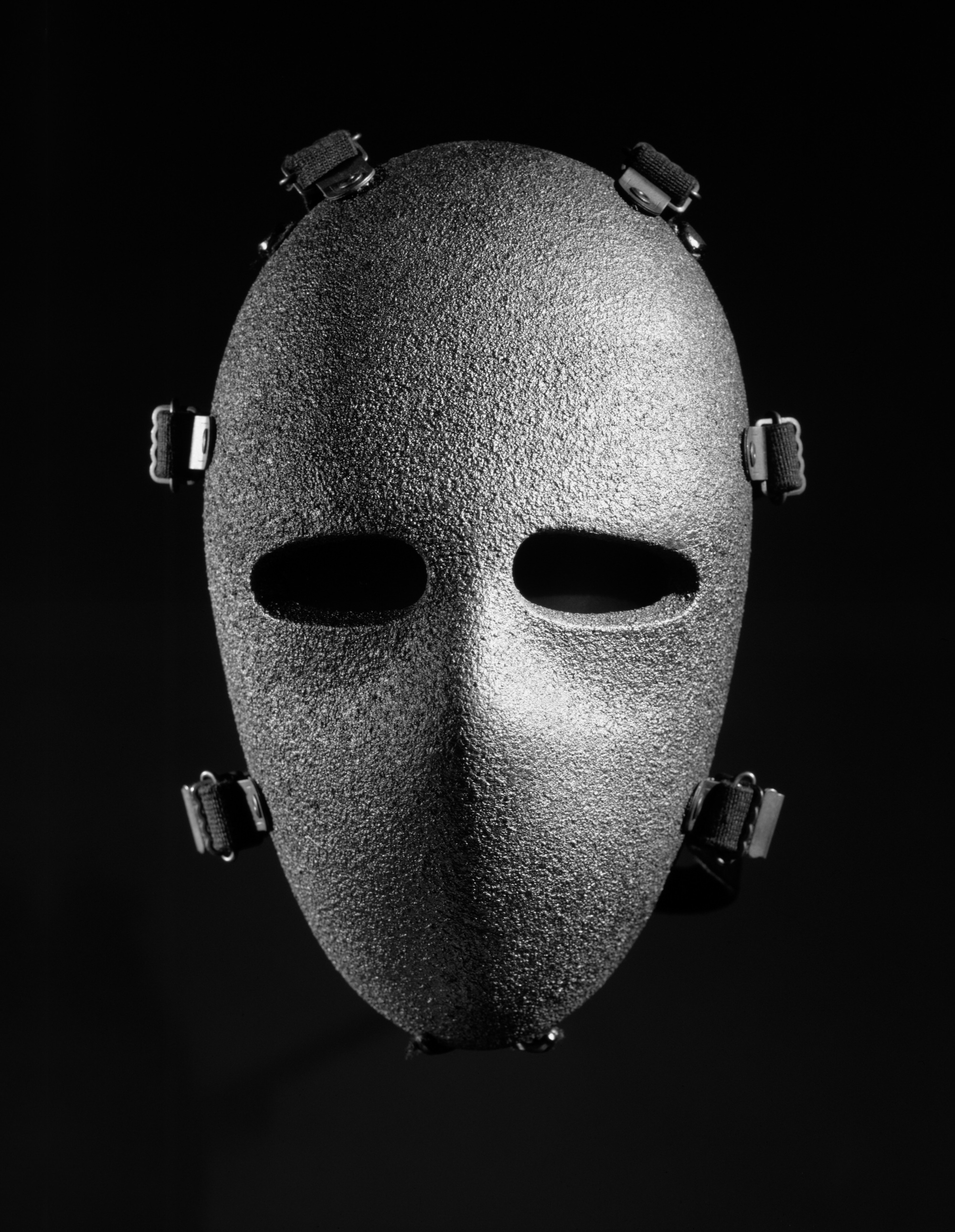

During the pandemic, the coalescences of viruses and human garbage is reflected in alarming reports on the prevalence of COVID-19 among both incarcerated people and correctional facility staff.5 These reports often focus on the implications for communities that people return to, thereby eliding the conditions in correctional facilities that all but ensure the spread of infectious diseases.6 They also overlook the way that masks have been used in correctional facilities long before the pandemic, an omission that renders invisible the way that this carceral use of masks influences perception. For instance, the mask from circa 1875 pictured below (Fig. 1) was worn by prisoners in solitary confinement when outside of their cells in order to enact complete isolation.

Figure 1. Calico hoods. Picture taken at the Old Melbourne Gaol, Australia by Ciell. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

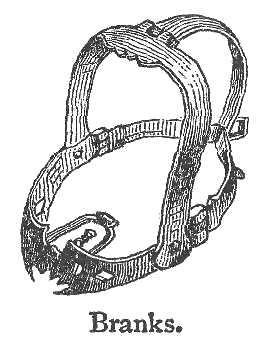

Similarly, the scold’s bridle (Fig. 2) was a tool that suppressed the wearer’s tongue and was used as an implement of humiliation and torture for those forced to wear it in public. This was also a gendered implement as it was primarily used on women, making it a state intervention into women’s speech.

Figure 2. Scold’s bridle. Illustration from 1908 Chambers’s Twentieth Century Dictionary. Branks, n. a scold’s bridle, having a hinged iron framework to enclose the head and a bit or gag to fit into the mouth and compress the tongue. By Rev. Thomas Davidson 1856-1923 (ed.) - Chambers’s Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Today, even prior to the pandemic, correctional facilities and law enforcement officers in the United States routinely used a range of masks to prevent a person from spitting on and/or biting officers. Spit hoods, also referred to as spit socks, came under scrutiny following the asphyxiation of Daniel Prude by the Rochester police.7 These hoods reportedly came into increased use during the COVID-19 pandemic when the risk of infection was greater. There are a variety of masks currently available on corrections suppliers’ websites, including: the Ripp Restraints Protective Mask,8 the spit sock hood,9 and the InnoShield 8K™.10

The use of such disposable face coverings, even before the pandemic, reinforces the notion of the detained or arrested person as potentially infectious and/or dangerous. Jails and prisons have the explicit mission of maintaining safety and security, with the common greeting being “have a safe tour.” In the context of a pandemic, such notions of safety and security are expanded to the virologic risk that is seemingly built into jails such as those in New York City, where most incarcerated people are housed in open dorms with 53 other people. They are filthy and crowded even in the best of times, making them truly perilous in the face of a pandemic.

This points to the accepted view of correctional facilities in the United States as wastelands. This is multiplied in the New York City jails, which are literally rooted in the refuse of prior centuries. They are not only places where humans (staff and incarcerated people) are made excess and expendable, but they also take an enormous environmental toll, as they generate tremendous amounts of waste, particularly because they primarily house people awaiting trial so are characterized by a constant churn of intakes and releases. Prior research and media coverage have highlighted the health effects of correctional facilities being located on toxic and/or contaminated sites, but there has been less recognition of the environmental toll of mass incarceration itself.11 While this is beginning to change with reports of high levels of correctional facilities’ water pollution, power plant construction, and electricity usage, calls for the end of mass incarceration have largely been situated around human rights alone.12

Nevertheless, today the United States is facing three seemingly distinct crises – a pandemic, world-altering climate change, and racialized mass incarceration. And yet, they are deeply imbricated. We must consider how these can be held together to tell a cohesive story about what it means to have a disposable population made to wear disposable masks on a site of disposal.13 To start, it must be recognized that this nexus does not remain neatly within correctional facility walls, but rather that carceral imaginaries and logics are visible across the pandemic and in responses to it. For instance, calls for people to wear masks were often read as dichotomic issues of compliance/autonomy, control/resistance, and discipline/freedom. These carceral binary oppositions, when applied to the pandemic, stand in contrast to notions of collectivism, relationalities, and care. Such carceral themes are similarly evident in state responses to non-compliance with mask regulations, as law enforcement officers have served as the ultimate executors of new public health regulations.

The thinking together of carcerality, waste, and infectious disease calls for a generative and sustained intervention. These nodes have been enmeshed for so long that their borders are no longer clear. Instead, there is a bleeding of meaning that coats masks in the carceral imaginaries of control, protection, and compliance. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the long history of the forced masking of incarcerated people does not remain neatly tucked behind bars. Instead, we face a messy tangle of governmentalities that announce themselves in the language of disease and carceral control while eliding their waste – human and otherwise. The spread of COVID-19 in the New York City jails results not only in disproportionate health effects, but also in increased duress to plead guilty in order to end the perilous wait for trial. During the pandemic, conditions such as these have contributed to Black Lives Matter protests calling for an end to police violence and racialized mass incarceration. Such pleas for the abolition of carceralities have implications far beyond the criminal justice system, as they also call to task the carceralities lodged in Western paradigms of disease control and mass environmental destruction. Together, these interconnected crises illustrate the high stakes of the status quo and the potentialities for radical change.

About the authors:

Ariel Ludwig previously worked in the New York City jail system and returned there to complete her dissertation research. She is a recent graduate from Virginia Tech’s Science and Technology in Society program. Currently, she is a researcher working at the intersection of health and the criminal justice system. Her current work serves to advance feminist, abolitionist Science and Technology Studies.

Jessica Brabble is a second-year history MA student at Virginia Tech. She is currently studying the connection between eugenics and the infant mortality movement in the rural South of the USA. Her work on medical history and popular culture is published in Nursing Clio and All of Us. In Fall 2021 she will be joining the College of William & Mary as a doctoral student in history.

E. Thomas Ewing is a professor of history at Virginia Tech, with research and teaching interests in the history epidemics, medical history, and data in social contexts. His research on the history of epidemics, including Russian flu (1889) and Spanish flu (1918), has been published in Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, Current Research in Digital History, Computer IEEE, and Medical History.

More information about their Flu Mask research can be found here: https://sites.google.com/vt.edu/flumasks/home.

References:

1 Fieldwork in the New York City jails was completed by Ariel Ludwig.

2 Schoenfeld, Heather. Building the prison state: Race and the politics of mass incarceration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

3 The City of New York. (2017) “NYC Department of Correction at a Glance: Information through all 12 months of FY 2017.”; The City of New York. (2020) “New York City Department of Correction Uniform Personnel Demographic Data.” The City of New York.; New York City Independent Budget Office. (2013) “NYC’s Jail Population: Who’s there and why?”.

4 Steinberg, Ted (2010). Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York. New York: Simon & Schuster.

5 Closson, Troy and Bromwich, Jonah. “‘A Ticking Time Bomb’: City Jails Are Crowded Again, Stoking Covid Fears.” The New York Times. March 10, 2020.; Rempel, Michael. “COVID-19 and the New York City Jail Population.” Center for Court Innovation. Published November 2020.

6 The Legal Aid Society. “Pandemic in Prison.” The Legal Aid Society. Last accessed April 7, 2021. https://legaidsoc.shinyapps.io/pandemicinprison/

7 Watkins, Ali. “What Are ‘Spit Hoods,’ and Why Do the Police Use Them?” The New York Times. Published September 3, 2020 and updated September 8, 2020.

8 Handcuff Warehouse. “Ripp Restraints Protective Mask.” Handcuff Warehouse. Retrieved from: https://web.archive.org/web/20210407154340/https://www.handcuffwarehouse.com/ripp-restraints-protective-mask; SWS Group Corrections. “Spit Hood.” SWS Group, Inc. Retrieved from: /web/20210407154624/https://corrections.swsgroup.ca/products/hygiene-sanitation/spit-hood>

9 Handcuff Warehouse. “Spit Sock Hood.” Handcuff Warehouse. Retrieved from: https://web.archive.org/web/20210115184615/https://www.handcuffwarehouse.com/spit-sock-hood/

10 Bob Barker Company. “InnoShield 8K™.” Bob Barker Company. Retrieved from: https://web.archive.org/web/20210407155255/https://www.bobbarker.com/innoshield-8k?page=1

11 Greenfield, Nicole. “The Connection Between Mass Incarceration and Environmental Justice: The country’s prison industry has little regard for where its facilities are located—even if that means building on noxiously polluted ground.” NRDC: onEarth In-Depth. Published January 19, 2018; Poon, Linda. “How Mass Incarceration Takes a Toll on the Environment: Both prisoners and surrounding communities are affected by this under-studied issue.” Bloomberg CityLab. Published July 30, 2015.

12 Bernd, Candice, Loftus-Farren, Zoe, and Mitra, Maureen Nandini. “America’s Toxic Prisons: The Environmental Injustices of Mass Incarceration: The toxic impact of prisons extends far beyond any individual prison.” Moyers on Democracy. Published June 9, 2017.

13 Closson, and Bromwich, 2020; Javorsky, Nicole. “Climbing Jail Population and Second COVID Wave Renews Push to Release NYers Behind Bars.” City Limits. December 16, 2020.; Marcius, Chelsia Rose. “NYC jail dorms are becoming overcrowded, raising concerns over social-distancing as inmate population continues to climb.” New York Daily News. November 9, 2020

We can keep silent, but that doesnt mean we dont care / Interview with artist Tran Tuan

“We can keep silent, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care”

In early April 2016, a devastating environmental disaster happened along the central Vietnamese coastline. A steel mill constructed by the Taiwan-based industrial Formosa Plastics Group in Ha Tinh Province was said to be responsible for having leaked chemical toxic waste into the ocean. This incident had a tremendous impact on sea life, leaving an enormous number of fish dead and causing illness amongst the Vietnamese people who had been exposed to the ocean and fishes. The disaster was reported to the Vietnamese government, which did not respond until April 25—it kept silent for far too long. Silence is a key(word) of an interactive project initiated by the artists Tran Tuan and Ngoc Tu Hoang in reaction to the government’s lack of response to this huge environmental disaster. With this project, Tuan and Hoang reached out to communities most affected by the spillage to create face masks with fish decorations, to accompany the slogan: “We can keep silent, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care.” Originally, the bodies of dead fish served as imprints, and were later transferred into the face masks, depicting the double death of silencing – a dead toxic fish placed over one’s mouth. Regina Maria Möller has spoken to one of the artists on behalf of the Mask–Arrayed team to reflect on this provocative project in the face of the current return of the mask as a symbol of another disaster.

RMM: Tuan, perhaps you can firstly give us a little bit more background information about how it began, and the idea behind this project and its slogan.

Tuan: The project started with a group exhibition I curated, “Quay II,” which took place in “Then Café” in Hue from May 5–May 12, 2016. I invited sixteen artists, all working with different art forms and media, to respond to this environmental disaster, which caused this tremendous fish death. Hoang Ngoc Tu created the artwork “Day 32” for this exhibition, which was thirty-two face masks with imprints of a fish between their layers. These thirty-two masks reference exactly thirty-two days of silence about this crisis due to Vietnam’s censorship of information. With the opening of the exhibition, we broke this silence.

“Day 32” by Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

“Day 32” by Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

As the curator of the exhibition, I came up with the idea to expand Hoang’s contribution to an interactive project involving communities across Vietnam. We planned to have over 10,000 masks created across the country for a (silent) protest. This mask was the ideal tool to help the protestors to stay anonymous, to hide their identity, to protect them from tear gas, but also to send our message that we want to protect the health of the Vietnamese, our families, and friends. Our slogan was: “We can keep silent, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care.”

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

We were hoping to run this project undercover, but it was impossible to do so. We needed to spread the word by using social media to reach out to participants across the country and to be able to collaborate and connect with various activist leaders and organizations. Due to our public call in a country with information censorship, we were, of course too visible and eventually got arrested. Yet, we were able to reach out, and more than 8,000 face masks were produced and distributed by various organizations in major cities across Vietnam, for example, Hanoi, Saigon, Danang, and many others. Unfortunately, most of our production was confiscated by the authorities, and more than sixteen organizations were busted and their members arrested. Also, Hoang Ngoc Tu and I were questioned by the police.

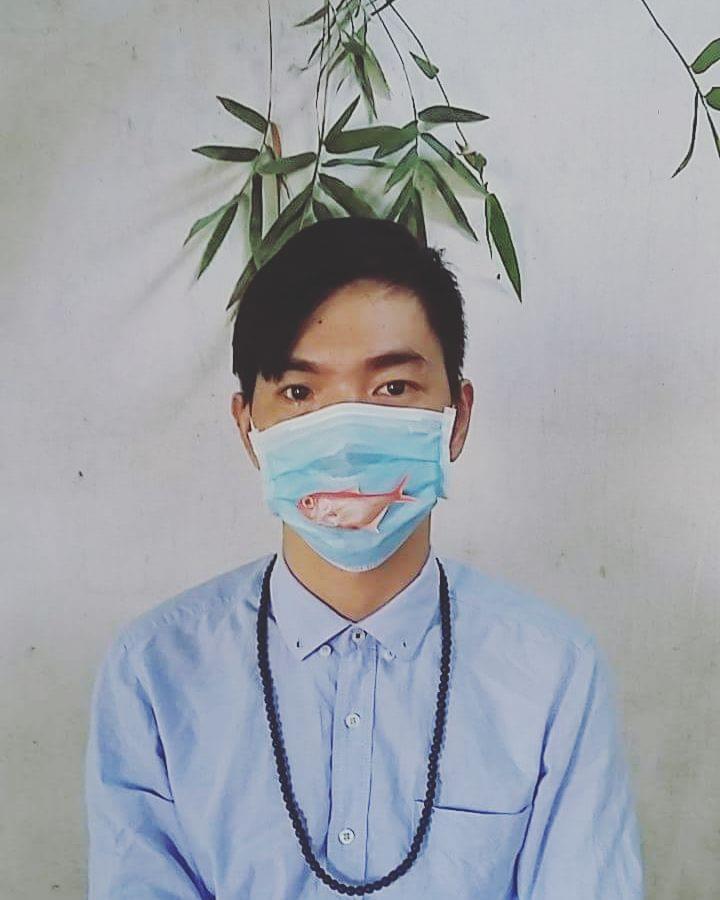

Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

RMM: What is it about the symbolic or artistic value of the face mask that attracted you to choose it as your instrument of expression?

Tuan: At a time when man-made production is endangering the health of humankind, the mask is the new symbol of our future, where our identity is obscured, and health is affected.

MA: You transformed the face mask into a powerful instrument to aid the silent political act of protest. Wearing face masks in Vietnam is a common practice—aside from medical reasons, in what other ways is the face mask used?

Tuan: As mentioned above, the mask can be used to hide one’s identity, which is quite strange, in my opinion, considering our vast global networking and worldwide communication with ever more advanced technologies. Humans seem to become lonely together—a communal solitude. Human bonds are very weak—immensely fragile. Imagine a society as a collective in which everyone is wearing the same single outfit—like the mask which we wear for health issues. But at the same time this “health issue” could also become (in some countries) a national strategy to silence voices—don’t protest because you are about to risk your life. I am obsessed with the concept of “singularity” in the spirit of Georg Cantor: “Great innovations only come true when people are not afraid to make a difference.” As an artist, I am interested in challenging the universal categories by exploring the internal paradoxes of our physical being. And it seems we are now approaching the era of technological singularity, which is being introduced with the concept of the “global mask.”

RMM: How did the community respond to your idea? And was there any reaction from the government?

Tuan: The community responded very strongly, even though our project was cut off. Many friends all over the country wore masks and took photos which were posted on Facebook and Instagram.

RMM: In the wake of the corona crisis, do you think that the face mask has emerged as an object that can or should be re-interpreted by artists, either for similar or different political reasons?

Tuan: Of course, after this pandemic the world will change, so as I said, the first step is the emergence of the concept of a “global mask.” It challenges the idea of “connectivity” and globalization.

RMM: Your project was dealing with the problem of toxic waste and industrial pollution, and you used the mask as a material and symbolic medium to draw attention to an environmental disaster that affected different communities in Vietnam. Now, four years later, these kinds of single-use face masks are in high demand globally and are slowly becoming a waste problem themselves. How do you position the materiality of the mask in relation to issues of waste? How can artists and community organizers respond to these most recent environmental threats that are resulting from the global state of emergency?

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Tuan: In my opinion, the question needs to rely on a philosophical point of view. The mask itself is an artificial product. It serves the needs of human consumption—our consumerism. It separates us from each other, and at the same time, it can bring us closer in terms of solidarity. Humans are creating disposable masks, as well as billions of other disposable products for millions of people in isolation at home. After this pandemic, this will be a significant problem that needs to be addressed by many governments. There will be technological solutions to handle it satisfactorily, for example, to find ways to reuse some of these articles. The question will be whether or not governments are willing to spend large amounts of money to invest in the disposal of waste that we produce in the future. Also, it is a question of whether we, as consumers, appreciate the value of the material we are using. This relates to a philosophical point of view, as I said. When people do not learn to appreciate the “true” value of the material they are using, then it is solely a commodity, and by adding more “virtual” value, it suits the consumer market even more.

For a long time, the world has suffered from a “supernumerary” crisis in rich countries and a “shortage” crisis in developing countries. Does this have anything to do with the actual value of the material we are using? And the masks raise the question: what is the most important for human beings nowadays: our health? Our identities? Or our immediate needs? Every individual will have a different answer.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.