“We can keep silent, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care”

In early April 2016, a devastating environmental disaster happened along the central Vietnamese coastline. A steel mill constructed by the Taiwan-based industrial Formosa Plastics Group in Ha Tinh Province was said to be responsible for having leaked chemical toxic waste into the ocean. This incident had a tremendous impact on sea life, leaving an enormous number of fish dead and causing illness amongst the Vietnamese people who had been exposed to the ocean and fishes. The disaster was reported to the Vietnamese government, which did not respond until April 25—it kept silent for far too long. Silence is a key(word) of an interactive project initiated by the artists Tran Tuan and Ngoc Tu Hoang in reaction to the government’s lack of response to this huge environmental disaster. With this project, Tuan and Hoang reached out to communities most affected by the spillage to create face masks with fish decorations, to accompany the slogan: “We can keep silent, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care.” Originally, the bodies of dead fish served as imprints, and were later transferred into the face masks, depicting the double death of silencing – a dead toxic fish placed over one’s mouth. Regina Maria Möller has spoken to one of the artists on behalf of the Mask–Arrayed team to reflect on this provocative project in the face of the current return of the mask as a symbol of another disaster.

RMM: Tuan, perhaps you can firstly give us a little bit more background information about how it began, and the idea behind this project and its slogan.

Tuan: The project started with a group exhibition I curated, “Quay II,” which took place in “Then Café” in Hue from May 5–May 12, 2016. I invited sixteen artists, all working with different art forms and media, to respond to this environmental disaster, which caused this tremendous fish death. Hoang Ngoc Tu created the artwork “Day 32” for this exhibition, which was thirty-two face masks with imprints of a fish between their layers. These thirty-two masks reference exactly thirty-two days of silence about this crisis due to Vietnam’s censorship of information. With the opening of the exhibition, we broke this silence.

“Day 32” by Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

“Day 32” by Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

As the curator of the exhibition, I came up with the idea to expand Hoang’s contribution to an interactive project involving communities across Vietnam. We planned to have over 10,000 masks created across the country for a (silent) protest. This mask was the ideal tool to help the protestors to stay anonymous, to hide their identity, to protect them from tear gas, but also to send our message that we want to protect the health of the Vietnamese, our families, and friends. Our slogan was: “We can keep silent, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care.”

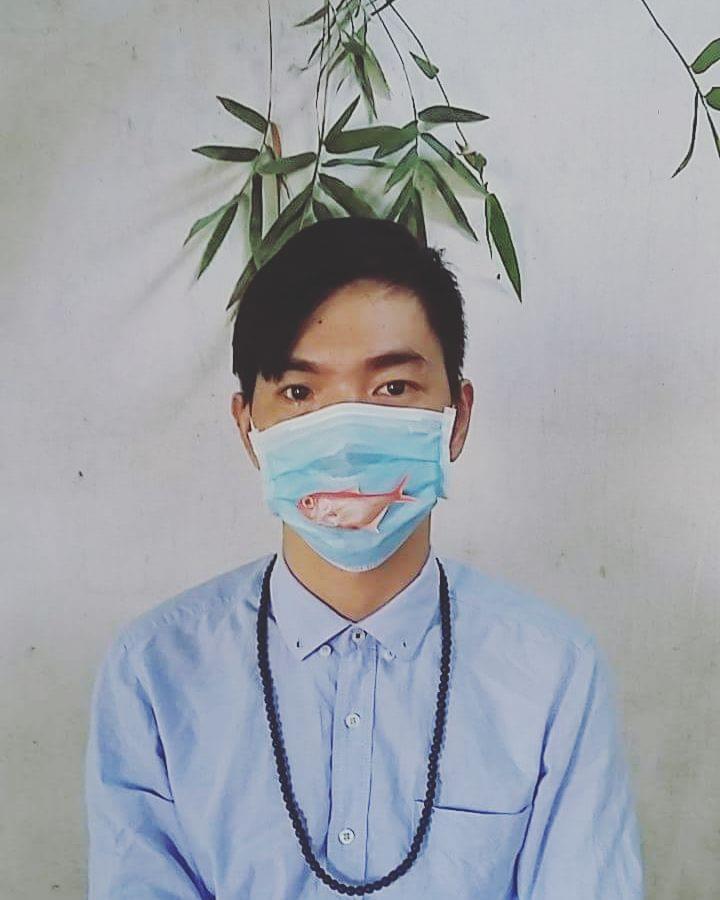

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

We were hoping to run this project undercover, but it was impossible to do so. We needed to spread the word by using social media to reach out to participants across the country and to be able to collaborate and connect with various activist leaders and organizations. Due to our public call in a country with information censorship, we were, of course too visible and eventually got arrested. Yet, we were able to reach out, and more than 8,000 face masks were produced and distributed by various organizations in major cities across Vietnam, for example, Hanoi, Saigon, Danang, and many others. Unfortunately, most of our production was confiscated by the authorities, and more than sixteen organizations were busted and their members arrested. Also, Hoang Ngoc Tu and I were questioned by the police.

Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Hoang Ngoc Tu. Image source: courtesy of the artist.

RMM: What is it about the symbolic or artistic value of the face mask that attracted you to choose it as your instrument of expression?

Tuan: At a time when man-made production is endangering the health of humankind, the mask is the new symbol of our future, where our identity is obscured, and health is affected.

MA: You transformed the face mask into a powerful instrument to aid the silent political act of protest. Wearing face masks in Vietnam is a common practice—aside from medical reasons, in what other ways is the face mask used?

Tuan: As mentioned above, the mask can be used to hide one’s identity, which is quite strange, in my opinion, considering our vast global networking and worldwide communication with ever more advanced technologies. Humans seem to become lonely together—a communal solitude. Human bonds are very weak—immensely fragile. Imagine a society as a collective in which everyone is wearing the same single outfit—like the mask which we wear for health issues. But at the same time this “health issue” could also become (in some countries) a national strategy to silence voices—don’t protest because you are about to risk your life. I am obsessed with the concept of “singularity” in the spirit of Georg Cantor: “Great innovations only come true when people are not afraid to make a difference.” As an artist, I am interested in challenging the universal categories by exploring the internal paradoxes of our physical being. And it seems we are now approaching the era of technological singularity, which is being introduced with the concept of the “global mask.”

RMM: How did the community respond to your idea? And was there any reaction from the government?

Tuan: The community responded very strongly, even though our project was cut off. Many friends all over the country wore masks and took photos which were posted on Facebook and Instagram.

RMM: In the wake of the corona crisis, do you think that the face mask has emerged as an object that can or should be re-interpreted by artists, either for similar or different political reasons?

Tuan: Of course, after this pandemic the world will change, so as I said, the first step is the emergence of the concept of a “global mask.” It challenges the idea of “connectivity” and globalization.

RMM: Your project was dealing with the problem of toxic waste and industrial pollution, and you used the mask as a material and symbolic medium to draw attention to an environmental disaster that affected different communities in Vietnam. Now, four years later, these kinds of single-use face masks are in high demand globally and are slowly becoming a waste problem themselves. How do you position the materiality of the mask in relation to issues of waste? How can artists and community organizers respond to these most recent environmental threats that are resulting from the global state of emergency?

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Tuan: In my opinion, the question needs to rely on a philosophical point of view. The mask itself is an artificial product. It serves the needs of human consumption—our consumerism. It separates us from each other, and at the same time, it can bring us closer in terms of solidarity. Humans are creating disposable masks, as well as billions of other disposable products for millions of people in isolation at home. After this pandemic, this will be a significant problem that needs to be addressed by many governments. There will be technological solutions to handle it satisfactorily, for example, to find ways to reuse some of these articles. The question will be whether or not governments are willing to spend large amounts of money to invest in the disposal of waste that we produce in the future. Also, it is a question of whether we, as consumers, appreciate the value of the material we are using. This relates to a philosophical point of view, as I said. When people do not learn to appreciate the “true” value of the material they are using, then it is solely a commodity, and by adding more “virtual” value, it suits the consumer market even more.

For a long time, the world has suffered from a “supernumerary” crisis in rich countries and a “shortage” crisis in developing countries. Does this have anything to do with the actual value of the material we are using? And the masks raise the question: what is the most important for human beings nowadays: our health? Our identities? Or our immediate needs? Every individual will have a different answer.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

Image source: courtesy of the artist.

About the artist: Tran Tuan is an artist born in Hue in 1981. He graduated from Hue College of Art with a degree in Traditional Decoration in 2006. His art practice is influenced by the untold stories of his family. Tuan has participated in many local and international exhibitions, such as “Nang Bong Nhe Tech” in 2011, “Altered Clouds” in 2012 and “Emperor Mushroom” in 2013. His series “Two Forefingers” was selected for the Singapore Biennale 2013. Throughout he has actively contributed to promoting art to a broader community in his hometown by establishing “Then Café,” where many art activities take place.

Video interview with Tran Tuan for the Singapore Art Museum

Tran Tuan’s work at Vin Gallery, Vietnam

Tran Tuan at Sàn Art

We would like to thank Veronika Radulovic for her help in contacting the artist.