“O make me a mask” is the ubiquitous call we hear all around us, echoing the opening line of the Dylan Thomas poem. Let us survey the prototype of a human face wearing an N-95 mask. Our mouths and noses are covered, our voice muffled and all scents except for that of our own breath—blocked. Our ears and eyes take in the sounds and sights around us. The eyes, head, and limbs become our main sources of expression toward others.

The N-95 mask is an ergonomic feature “designed to form a seal around the nose and mouth.” It protects those who wear it from inhaling small airborne particles, while also preventing the contamination of others. The macro perspective of this situation is mirrored in the way our surroundings these days are forcing us to separate from each other, creating a virtual border aimed to help us avoid infection. Much like the iconic Cone of Silence featured in the confidential conversations between Maxwell Smart and the Chief in the 1960s’ American sitcom “Get Smart,” this dual mechanism forces us to communicate with our senses muffled.

Figure 1: The “Cone of Silence” from the TV series Get Smart, Season 1, Episode 1 “Mr Big,” NBC, aired September 18, 1965. Source: “Cone of Silence,” Wikipedia.

The individual wearing a mask, concealed and protected by an object of use, can be described as “choked.” This sensorial limitation made me think of a passage in the Zhuangzi, an early Chinese philosophical text, which addresses the obstruction of what it defines as six senses (eyes, ears, nose, mouth, mind, knowledge). It treats them figuratively, arguing that dulling the keenness of perception makes room for harm.

Acute eyes make for keen vision;

acute ears make for keen hearing;

an acute nose makes for keen smell;

an acute mouth makes for keen taste;

an acute mind makes for keen knowledge;

acute knowledge makes for integrity. Whatever is the Way [dao 道] does not like to be obstructed.

If it is obstructed, then it becomes choked.

If it is unceasingly choked, then it becomes stagnant.

If there is stagnation, a host of injurious effects are born.

(Translated from Chinese by Victor H. Mair)1

The English intellectual Al Alvarez (1929–2019) is a bit more subtle. In the chapter “The Problem of Consciousness” in his book Night: An Exploration of Night Life, Night Language, Sleep and Dreams, he argues that subjective perception is an infinite intricate amalgam of the mental and the physical, the internal and the external. The individual wearing a mask, according to Alvarez’s viewpoint, would experience a mental change because “mental” is not a material entity but the way we experience our lives. But these days, our consciousness remains. Our senses are muffled, but we still, for now, have our minds.

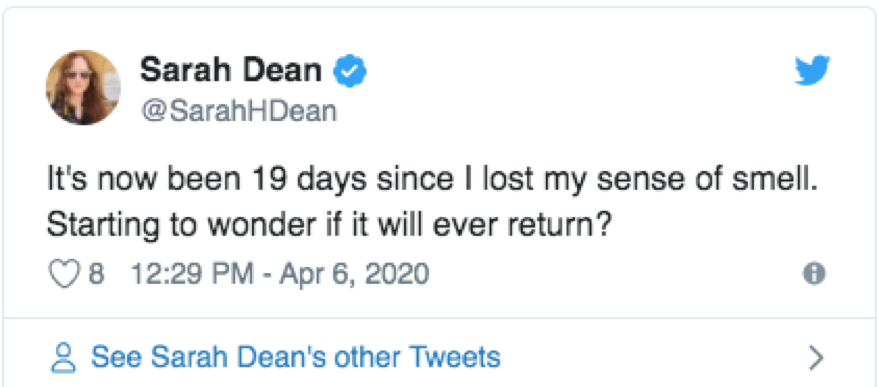

COVID-19 and its prevention methods are a sorrowful sensorial feast. Its onset symptoms may include a loss of smell and taste. Numerous testimonies by people diagnosed with the virus are starting to appear on social media. On April 6, CNN International Senior News Editor Sarah Dean Tweeted: “It’s now been 19 days since I lost my sense of smell. Starting to wonder if it will ever return?” On April 27, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention added the loss of smell, taste, or both to the list of COVID-19 symptoms.

Figure 2: Sarah Dean, Tweet Post, April 2020, 12:29 PM.

Scientists at the Weizmann Institute in Israel have developed an online platform to help individuals assess their olfactory sense in a five-minute test using household items, such as spice and vinegar. The platform, called Smell Tracker, “enables self-monitoring of an individual’s sense of smell—for the purpose of detecting early signs of COVID-19 or in the absence of other symptoms.” Currently, there are eight active strains of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. One of the goals of this research is to determine whether the loss of smell is a symptom of any of these strains. Struggling to breathe remains a main feature of the disease. The irony is noticeable, since its object of prevention, the N-95 mask, obstructs these two senses, while the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, FDA, warns us that the mask “can make it more difficult for the wearer to breathe.” Thus, the mask and the virus unify healthcare workers and patients under a similar symptomatic umbrella.

Our tactile sense is also affected [video]. According to Martin Grunwald, a psychologist at the University of Leipzig, Germany, touching ourselves is a “fundamental behavior of our species” (read the complete interview in Spanish here). It seems that, next to apes, human beings are the only species who spontaneously and incessantly touch their mouths, noses, and eyes—no less than twenty-five times an hour. While other species touch their faces for reasons such as hygiene, humans and certain species of apes may do so as a fundamental method to control emotions, autoregulate, concentrate, and even as a form of social signaling. This behavior is cardinal in our cognitive and emotional processes. Unfortunately, this is also how we transmit the virus from a surface onto our hands and into our bodies. The use of masks and gloves prohibits us from touching our face and narrows these innate behaviors.

Video 1: “Coronavirus: Why we Touch our Faces and How to Stop It - BBC News,” March 16, 2020, YouTube video, 2:31, posted by “BBC News.”

Professionals in various fields are making their best efforts to turn the N-95 mask into a quotidian, unobtrusive, easy-to-wear item. In addition to the highly-regulated mask, in Spain and Argentina, product designers and architects have constructed a face shield, an additional piece of protective equipment, aimed to “comfortably” fit the mouth, nose, and eyes. Others have designed special extension straps called Ear Savers, which aim to mitigate pain to the ears caused by the extended use of face masks. The Czech 3D printer company, Prusa Research, has created an open source face shield model for healthcare personnel, urging anyone with access to 3D printers to make them. In Italy, the physician Renato Favero has improvised an emergency ventilator mask for patients by converting a Decathlon Easybreath scuba mask. But no matter how comfortable the mask, our sensorial communication remains severed.

Those fortunate healthcare workers who are provided with sufficient protective gear have nearly complete sensorial obstruction. They wear tight-fitting goggles and masks, their grip pitting the face, indenting marks across it. Images of nurses and doctors in Wuhan and elsewhere in China taking their gear off after long shifts, their faces bruised and marked, have been published in People’s Daily, China and circulating on Chinese social media and news sites (see an article in English here). Similar photographs of healthcare workers around the globe, including the now-famous photograph of Italian Doctor Nicola Sgarbi, have also been published in European and American news outlets. For a moment it seems that it is not patients, but healthcare workers and their gear, that are functioning as the very personification of the virus.

Figure 3: People’s Daily, China, Tweet Post, February 2020, 02:00 AM.

Figure 4: Photograph of Dr. Nicola Sgarbi. Source: Fernando Alfonso III, “The Many Faces of Health Workers Around the Globe Fighting Coronavirus”, CNN online, March 22, 2020.

In her 1978 book Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag argues that the very name of a disease, for example “cancer,” symbolizes death with all its imagery, signifying a permutation between meanings. In the case of “COVID-19,” the N-95 mask becomes a metaphor for the loss of senses, it makes the virus tangible, draws an image of its perilousness, while making contagiousness visible. All of these are paradoxically manifested on the body of the healthy healthcare worker, rather than on the patient.

COVID-19 has rendered us immobile. Hospital patients struggling to survive are immobile. Those of us who remain in our homes by order are confined. But this immobility can also become a call to examine a new perspective. In his 1902 book The Intelligence of Flowers, Flemish Nobel Prize-winner Maurice Maeterlinck marvels at the plant, bound to the ground and condemned to immobility. He praises “the energy of its obsession, as it rises from the shadows of its roots to organize itself and to blossom in the light of its flower” (p.2). This is the opportunity that lies in what may feel like stagnation, limitation. The invitation to reorganize our sensibilities, to act, to keep in motion and transcend, engaged together with our new friend, the mask.

About the author: Noa Hegesh is a postdoctoral fellow the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, where she works on the history of sound in Early and Early Medieval China. Her research explores musical thought and the use of sound measuring as a technology in astronomy, metrology, and prognostication. She is interested in the ways we think about sound and the many ways we experience it.

References:

1 Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu, trans. Victor H. Mair (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1998), p. 275.