Introduction

Are Asians natural mask-wearers? During the current Corona crisis, a renewed interest in the mask-wearing culture of the “East” has emerged, particularly among American and European media outlets which portray East Asian countries as “masked societies” that were already using sanitary masks before the global pandemic. But scholars in and outside of Japan have also explained the Japanese mask-use culture in terms of Japanese people’s cultural characteristics.1 In this conversation, Jaehwan Hyun and Tomohisa (Tomo) Sumida discuss the material history of mask-wearing in Japan and South Korea, while acknowledging cultural proclivities. They consider the use and circulation of masks across national borders between the two countries, and debate differences in social attitudes. Instead of essentializing mask-wearing practices as being part of an East Asian or national culture, the two historians shift the focus and show how mask usage is closely linked to the issues of environmental pollution, standardization, and public trust in the two countries.

Environmental Histories of Masked Societies

Jaehwan: Let’s begin our conversation by talking about the origin of mask-wearing in Japanese and South Korean contexts. Since South Korea was a former colony of the Japanese Empire (1910–1945), early twentieth-century Japanese history would be a useful starting point for narrating both countries’ experiences.

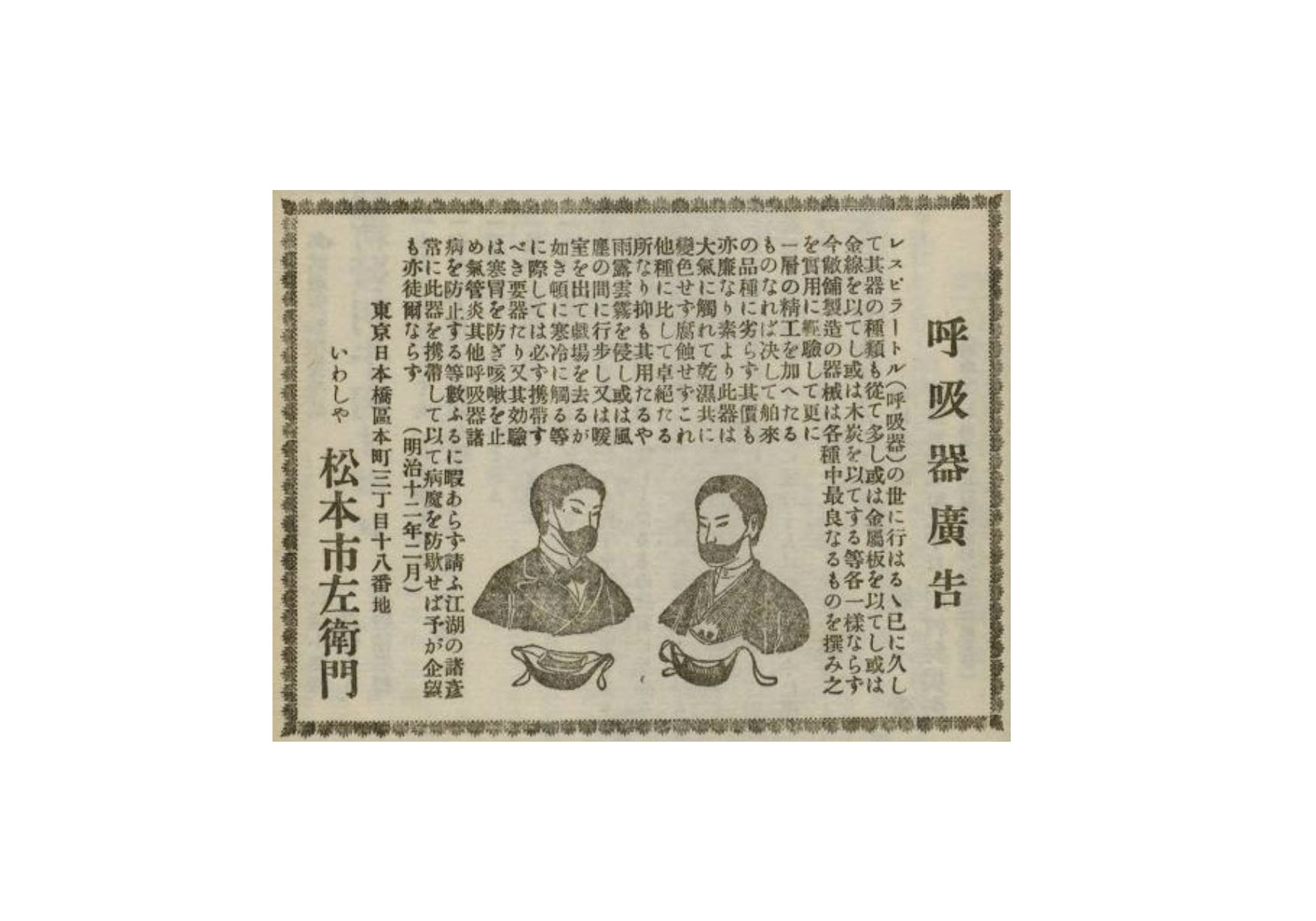

Tomo: I found the “Jeffreys’ respirators” in several medical equipment catalogues published in the late 1870s. This black “respirator” with a metal piece was originally invented in London in 1836 for patients with lung disorders, to add moisture and warmth to intake air. A Japanese advertisement in 1879 emphasized its effectiveness in tackling sudden temperature changes (such as when you exit from a theater), preventing catching a cold, having a cough, and suffering from respiratory diseases (Figure 1). Those claims had been made in advertisements published in other countries.

Figure 1: “Advertisement for Respirators,” by Iwashiya Matsumoto Ichizaemon, Tokyo, 1879.

Those respirators were also used in occupational and public health contexts. A hygienist, Tsuboi Jiro, mentioned respirators in an article on mining health in 1890. The respirators entered public health at the first-ever encounter with a plague of pests in Japan in the final years of the nineteenth century. This happened before the colonization of Korea. I am curious, what was going on in Korea at that time? Had Koreans already used respirators before colonization or not?

Jaehwan: I am not sure, but the first colonial government’s response to the 1910 Manchurian plague mainly focused on exterminating rats. At that time the quarantine authorities considered the disease was a bubonic ailment, not a pneumonic condition.2 I couldn’t find any evidence that Koreans wore masks against infectious diseases before colonization. I’ll have to leave that question to Korean medical historians working on the period.

Tomo: After the 1918 flu, masks became common in Japan. Some people wore masks after the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. My grandmother told me that, in the 1930s, her grandmother put on a handmade white mask over her on windy days to protect her from street dust. Another relative of mine wore masks when he went to school on cold mornings.3

Jaehwan: This is quite fascinating! The South Korean experience is closely connected to the Japanese one, despite different trends of ups-and-downs in using masks. As part of the Japanese Empire’s quarantine regime, colonial Koreans were forced to wear sanitary masks during and after the influenza pandemic of 1918–19. The colonial government advised Koreans to wear masks as a crucial preventive measure for the first time.4 Like their colonizer, colonial Koreans also began to wear masks against seasonal flu and dust throughout the colonial period from then on. In 1935, a Korean colonial columnist complained about the masked crowd on Keijo’s (currently Seoul) streets, describing them as a sort of eyesore.5

After Korea became independent in 1945, the South Korean government as well as medical authorities promoted mask-wearing as a response to rising concerns about environmental problems. For instance, in 1970, when the Korean government imported Japanese regulatory measures to cope with environmental pollution, the practice of mask-wearing against air pollution was also introduced to this country. Seoul’s city government distributed “pollution masks” to its citizens, but they did not become part of everyday life.6 Two decades later, the government and medical authorities again encouraged Koreans to wear masks against pollen allergies and yellow dust—so-called “Asian dust” that originates from the deserts of China and Mongolia in the spring. There has been a long debate about the efficacy of masks against viruses within the domestic medical community since the 1930s, but so far I haven’t found any criticism of using masks to protect yourself against pollen allergies and air pollution, prior to the 2000s.

Tomo: In Japan, air pollution was most severe in the 1960s. The region affected most was the area around the Yokkaichi petroleum complex in Mie. The local government there distributed yellow masks with activated carbon to school children, claiming that these masks were similar to those used by the London Police.

Japanese people have been getting used to wearing masks. Since the 1980s, cedar pollen allergy in spring has become a frequent ailment. Today, almost half of Japanese people suffer from it. A more common experience is shared at school lunch time. When kids serve themselves dishes, they wear white caps, smocks, and masks.

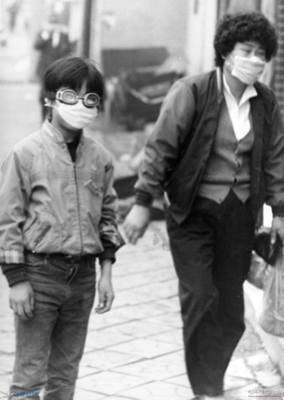

Figure 2: A mother and her child wearing masks to protect themselves from tear gas which police used against young demonstrators on April 17, 1985. Photo taken by Kyunghyang Shinmunsa. Courtesy of Open Archives of the Korea Democracy Foundation.

Jaehwan: I remember that I wore a sort of smock while serving dishes at school lunch time, but didn’t wear a mask at all. Mask usage remained limited to protection against the cold in South Korea, I think. In warmer seasons, masks were probably used mainly by student protesters against the military dictatorship in the 1980s. It was also common that non-protesters wore masks to protect themselves from tear gas used by the authoritarian government before the democratization of the country in 1987 (Figure 2). It was only with the rising fear of the health risk of micro dust particles in the late 2000s, which I will talk about in detail later, that Koreans began to wear a particular type of mask called “yellow dust masks” on a regular basis (see Hyun’s “Living with Masks” on this website).

Environmental problems remain the main reason why masks have repeatedly appeared in the postwar history of the two countries. I am curious why the Korean government has distributed masks to its citizens more often than regulating pollutants produced by petrol engines and factories.

My hypothesis is that the masks might have been the government’s means of avoiding responsibility for protecting citizens from the outcome of their state-led and -centered industrialization. By putting masks on people’s faces, governments could attribute the responsibility of their own health problems caused by environmental pollution to individuals. This could be applied to the Japanese experience.

Tomo: Interesting! I think it’s worth studying this hypothesis and looking for more evidence – that’s the thing we have to address. In any case it is evident that the history of mask-wearing in the two countries should be situated within an environmental history context.

Mask Standards and Guidelines

Jaehwan: The history of science and technology has taught us that standardization procedures are powerful tools. So, I think it would also be worth discussing national differences in technical mask standards.

Tomo: In Japan, official standards have been formulated for dust masks since 1988, but not for medical masks. For non-medical sanitary masks, the mask makers set two voluntary standards around 2010. One regulates display and advertising, to prevent misinformation. Another one concerns safety and cleanliness (hygienic production).

The lack of standards for sanitary masks in Japan made it possible for the rough recommendation in the current pandemic to wear masks, without further elaborating what kind of masks. Some countries which do regulate medical masks need to preserve them for their medical workers, thus they have created a new term: “cloth face coverings.” The Japanese government has never made wearing masks compulsory. I was surprised that so many countries have made it mandatory, including the United Kingdom, since June.

Jaehwan: The South Korean government made face masks mandatory on May 26, a month after some state governments in Germany introduced Maskenpflicht (a mask requirement rule).7 Like Japanese citizens, Koreans had also worn masks without any legal enforcement until then. A difference also exists, however. I had a quick look at the mask-wearing guidelines in Japan and Taiwan, and found that both those governments were quite reluctant to encourage non-symptomatic citizens to wear face masks, even though they tried to meet the domestic demand for masks efficiently and timely. In contrast, on March 4, when the number of cases had rapidly increased, the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Korean CDC (renamed the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency on September 12, 2020), recommended that non-infected people should also wear face masks.

The Korean government’s “masko-philism” might have stemmed from its recent “war against micro dust particles.” With the introduction of fine particular matter (PM10 and PM2.5) regulations, the government established national standardization and related procedures for masks as medical equipment in 2008. The classification of KF80, 94, and 99 standards was established by their rate of blocking the fine particles. The government encouraged Koreans to wear these standardized masks when there was a very high concentration level of micro dust particles or yellow dust. Their unproven belief that the yellow dust coming from mainland China is the primary source of particle pollution in South Korea was only to be expected.

The mask standards seemed to work in powerful ways. When the yellow dust season was on its way, people looked for KF94 masks in the belief that the higher number would protect them more from the invisible threats of micro dust particles. Korean historians Hyungsub Choi and Heewon Kim call the way that wearing KF94 masks against the micro dust particles worked as a “reserve training” for practicing how to wear hardly breathable KF94 masks in the time of Corona (Choi and Kim 2020). The KF standards shaped Korean mask-wearing guidelines as well, since the government’s recommendation relied on the classifications of KF80 and 94. They said that KF94 masks should be used when taking care of people with COVID-19 infection, while KF80 is used more widely in the case of people with underlying symptoms.

Tomo: Another commonality! Irrespective of whether standards are dubious or clearly established, national differences in mask-wearing guidelines and regulations can only be understood when considering national mask standards, at least in the two countries.

Public Trust and Expertise in Mask-Wearing

Jaehwan: We’ve talked about the origin of, and the current government guidelines for, mask-wearing. Let’s return to our initial question: why have Japanese and Koreans worn masks from the very outset of the Corona pandemic? The Japanese case is interesting because there has been no direct regulation from the government for its citizens to use masks against viruses, although there were some recommendations.

Tomo: Many people in Japan have worn masks every winter and spring to prevent flu and the pollen allergy, respectively. People with a pollen allergy, including me, can feel how masks work to block pollen. For viruses, we cannot feel the effectiveness of masks, other than knowing they prevent droplets spreading.

Japanese people, they say, tend to conform to society. Maybe people there wear masks because other people do. In such a situation, the masks’ materiality plays the role of demonstrating your conformity to others. Can you think of any scientists who recommended wearing masks in South Korea?

](/images/upload/meeting.png)

Figure 3: The meeting that declared a state of emergency, April 2, 2020. Source: Website of the Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet

Jaehwan: The Korean CDC’s director Jeong Eun-Kyeong is the most famous scientific figure in the pandemic scene. She is more like a technocrat than a medical researcher, but she’s widely supported as the leading expert by grassroots citizens, like Christian Drosten in Germany. Jeong regularly makes statements encouraging Koreans to wear masks as a normal part of the national quarantine policy after a massive outbreak in March.

Tomo: The government and medical authorities did recommend wearing masks, but I think people don’t only wear masks because of the official recommendation. A Nobel Prize Laureate and keen jogger, Yamanaka Shinya at Kyoto University, repeatedly advised joggers to wear masks.

Jaehwan: A peculiar feature of the Korean pandemic scene is that both the government and citizens seem like mask fanatics! When staying in Seoul for some weeks in May, I found that the social distancing rule did not work at all—in fact, it’s almost impossible, given the population density of Seoul and its suburban area—but instead, everyone was masked. In contrast to Japanese people, Koreans seriously check the droplet filtration rate when purchasing masks, because they believe that masks are effective against viruses. In early June, a new thinner type of KF mask called KF-AD (anti-droplet) has been devised and supplied by the government in order to let people wear masks in the incoming hot and wet summer. The initial supply of two hundred thousand masks quickly sold out, so the government now aims to make one million KF-AD masks per day before late June. It’s worth noting that the South Korean President Moon Jae-In has kept wearing a KF94 mask since January 28, regardless of the Korean CDC’s first mask-wearing guidelines recommending that healthy people should not wear masks outdoors.8

Citizens distrust politicians, institutions, media outlets, and even experts. Indeed, the level of social trust in South Korea is the lowest among the OECD member countries.9 If Koreans trust anything in these Corona times, it will be the artifact—masks—not the government or scientific experts. I suppose that the materiality of masks covering faces is something tangible, and hence conjures up trust among people who can literally take protection into their own hands.

Tomo: We should not forget to think about “expertise” in the history of masks as well. There has been much disagreement about the effectiveness of masks as a public health measure from the late-nineteenth century onwards. Similar disputes emerged when the CDC and WHO changed their mask-wearing recommendations on April 6 and June 5, 2020, respectively.

The current uncertainty over the effectiveness of masks, particularly everyday masks, has led to a growing number of studies in recent months, but more work has to be done in this regard. The same counts for a historical treatment of face masks. We have a lot of work to do on this, even after the pandemic has ended.

Jaehwan: Yes, that’s why we need to keep having this kind of conversation across national borders and disciplinary boundaries. We need to know more about how people live with masks in different social, political, historical, and environmental contexts. We should study the diverse living experiences with, and materialities of, masks together with medical historians, sociologists, anthropologists, epidemiologists, industrial engineers, and citizens.

About the Authors:

Jaehwan Hyun is a historian whose work explores transnational connections of scientists from Japan, South Korea, and the US as well as the role of materiality in shaping such exchanges. One of his projects investigates how the materiality of diving masks and other equipment shaped trans-pacific science and the lives of the sea women after World War II. Jaehwan believes that narrating the living experience of the diving-mask users will help us seek a way to live with masks “wisely” in the corona pandemic. Now he is making an effort to create a research collective in studying the making of “masked societies” in East Asia with other East Asian historians of science and scholars of science and technology studies (STS).

Tomohisa Sumida (住田 朋久) graduated from the University of Tokyo with a Master’s degree in the History of Science and is currently working for a Japanese public think tank. His work explores the social dimension of science as it relates to topics such as nature conservation, air pollution, and pollen allergies. In his paper “Covering Only the Nose and Mouth: Towards a History and Anthropology of Masks”, published in the journal Gendai Shiso [Contemporary Thought] in May 2020, the mask is at the center of inquiry. Translations of this article into English, Chinese, and Korean are in work.

References:

1 For example, see Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko, Illness and Culture in Contemporary Japan: An Anthropological View (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984) and Horii, Mitsutoshi, “Why Do the Japanese Wear Masks?: A Short Historical Review,” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies 14, no. 2 (2014). Meanwhile, Korean scholars have not paid attention to mask-wearing practices until recently. It is a welcome development that young scholars working in the fields of the history of technology and STS have begun to look into the historical and sociological nature of mask-wearing in this country. See Choi, Hyungsub, and Kim, Heewon, “K’orona shidaeŭi chungyohan samul, masŭk’ŭe taehan modŭn kŏt [A Face Mask, an Important Artifact in Times of Corona: The Everything of Masks]”, Science Magazine Epi 12 (June 2020): 54–68.

2 Shin, Kyuhwan, “Che1,2ch’a manju p’yep’esŭt’ŭŭi yuhaenggwa ilcheŭi pangyŏk’aengjŏng (1910–1921) [The First and the Second Pneumonic Plague in Manchuria and the Preventive Measure of Japanese Colonial Authorities (1910–1921)],” Uisahak [Korean Journal of Medical History] 21, no. 3 (December 2012): 449–476.

3 Sumida, Tomohisa, “Bikō nomi o ōu mono: masuku no rekishi to jinrui-gaku ni mukete [Covering Only the Nose and Mouth: Towards a History and Anthropology of Masks],” Gendai shisō [Contemporary Thought], 48, no. 7 (May 2020): 191–199.

4 Chōsen Sōtoku-fu (Government-General of Korea), “Ryūkō-sei kanbō no rekishi shōkō oyobi yo-bō [The History, Symptoms, and Prevention of Influenza],” Chōsen ihō [Korea Bulletin], January 1919: 98.

5 Yuh Woon-Hyung, “Pogi kŏbuk’an masŭk’ŭdangdŭl [Awful Looking Masked Crowd],” Chosŏn chungang ilbo[Chosun Chungang News], December 27, 1935, p. 3.

6 “Ch’orahan kigu, yesan [A Miserable Organization and Its Budget],” Kyŏnghyangshinmun [Kyunghyang News], August 1, 1970, p. 3.

7 This conversation happened in early June and does not reflect on the recent change of mask regulations in South Korea. On Korea’s National Liberation Day (August 15), massive anti-government demonstrations, led by conservative pastor Jun Kwang-hoon and his believers at Sarang Jeil Church, were held in the Gwanghwamun area of downtown Seoul. The demonstrations led to the country’s largest COVID-19 outbreak since March. As a result, the government introduced stricter guidelines, such as wearing face masks both indoors and outdoors in the Seoul Capital Area.

8 The government’s preoccupation with mask-wearing has become stronger. New guidelines introduced after the Liberation Day Corona outbreak oblige 25 million Koreans residing in the Seoul Capital Area to wear masks even when outdoors.

9 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Korean Development Institute (KDI), Understanding the Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions in Korea (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018).