I started studying the practice of public mask-wearing more than a decade ago. My interest in this specific practice was triggered by the 2009 ‘swine flu’ (H1N1) pandemic. I am originally from Japan, but I have lived in the UK since 1996. During the 2009 pandemic, I saw a number of media images of Japanese people wearing masks in public, and found that it was an interesting contrast to the lack of any such habit in the United Kingdom.

Figure 1: Swine flu leaflet, United Kingdom, 2009. Copies of this leaflet were delivered to all UK households as part of the UK government’s public health awareness campaign that began in May 2009. Maker: National Health Service. Source: Science Museum, London

At that time, my research question was: ‘Why do Japanese people wear masks?’ and I studied the history of mask-wearing in Japan. In 2011 I also carried out a small-scale survey in Japan, asking people in the streets of Tokyo why they wear masks. The fruits of this research were two academic articles in English and one monograph in Japanese.1 In those works, I pointed out that the popularisation of public mask-wearing preceded the scientific evidence of its effectiveness, and conceptualised it as a form of ‘risk ritual’ which functions to restore wearers’ psychological stability by providing them with a sense of control in a seemingly uncontrollable circumstance.

The outbreak of Covid-19 has forced me to renew my interest in the practice of public mask-wearing. My publications on masks were picked up by journalists, and I have been interviewed in a number of media since the beginning of 2020. Journalists usually ask me this question: ‘Why do people in East Asia wear masks?’ and ask for my view on the cultural aspect of mask-wearing.

In recent months, I have been wondering whether we have all been asking the right question. When we ask why people in East Asia wear masks, we are gazing at East Asia from the West, where public mask-wearing is not the norm. I have realised that this Western curiosity towards East Asian public face covering was tacitly authorising the Western cultural norm of face exposure in public as the universal standard of public civility.

Since this realisation, I have been asking a different question: ‘Why don’t people in the West wear masks?’ I have found this a more interesting question, one which could challenge the cultural hegemony of Euro-American modernity.

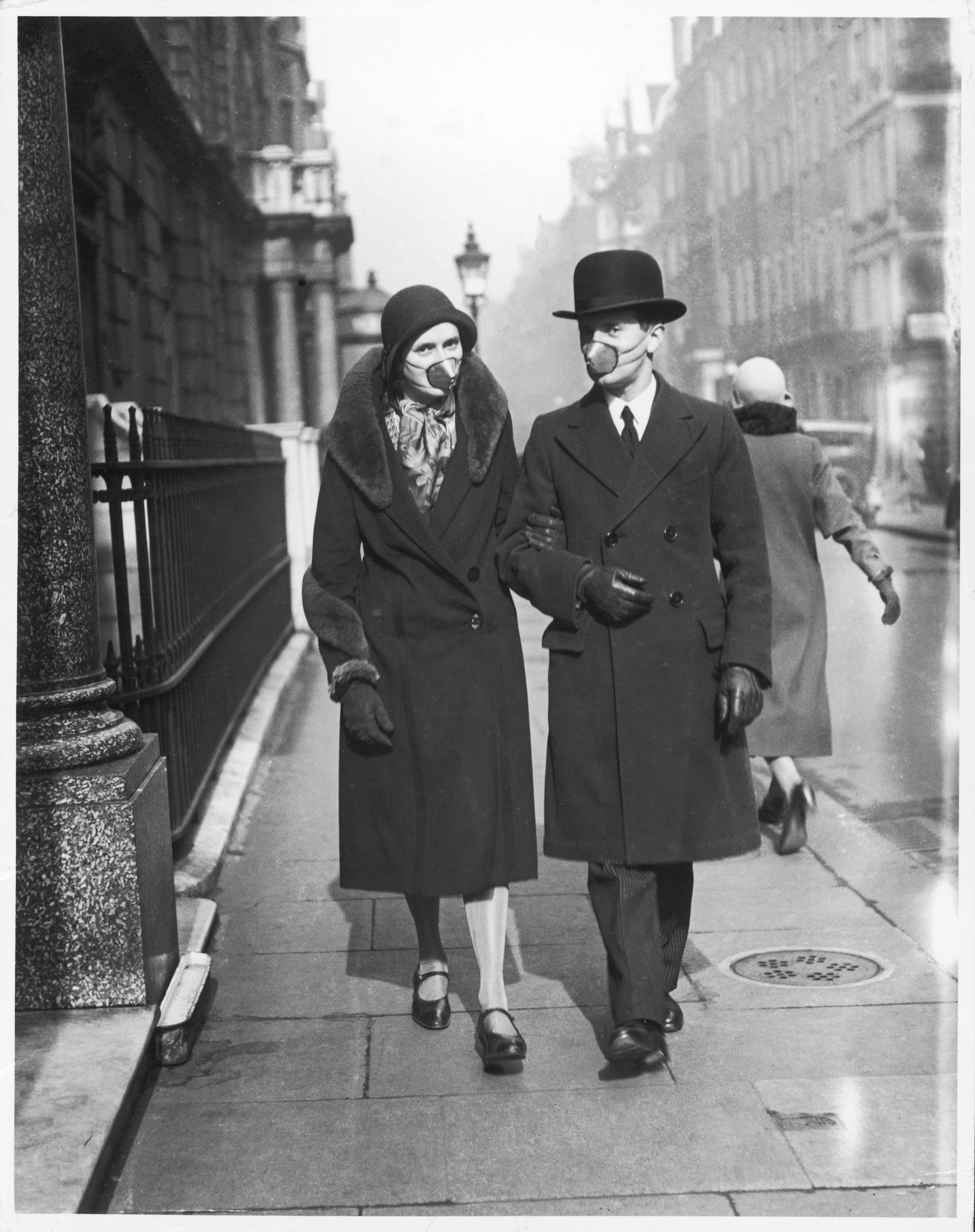

Mandatory mask wearing in public spaces was first introduced in Western nations as a public health policy during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. This was also the case in Japan at the time, and since then wearing a mask in public has been incorporated into Japanese people’s daily routine. In contrast, this practice mysteriously disappeared in the West after the pandemic. Why? This is an interesting historical question, for which I do not have any answer.

Figure 2: Another bout of flu that killed so many in Britain after WW1 lasted from 1929 to 1937. People wore surgical masks or stylish nose caps as this couple demonstrates. Source: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Now, a century later, mask-wearing in public has been re-introduced in the West as a result of the Covid-19 outbreak. Living in the UK, I have been watching this development with great interest. I would like to offer three observations that shed light on some factors connected to mask-wearing in the West.

- ‘Science’ as a human activity: The effectiveness of mask-wearing as a public health measure against infection was not initially recognised by Western governments and the WHO, partly due to the lack of scientific evidence. During the first wave of Covid-19, however, it became more apparent that there were actually lots of scientists who endorsed mask-wearing in public. Many Western governments and the WHO eventually changed their policies on mask-wearing. This issue reminds us of the fact that ‘science’ is a human activity which involves disagreements, negotiations, decision-making, and changing conclusions.

- Face-coverings and civil liberty: What we hear about public mask-wearing in the US seems to be a déjà vu from the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. It has been widely documented that, during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, when some cities enforced mandatory mask-wearing in public, many people refused to wear masks, claiming that it was a violation of their civil liberty. Today in the US, people’s differing attitudes towards mask-wearing seem to reflect an ideological divide. On the eve of the Presidential election, we saw images of unmasked Trump supporters and masked Biden supporters. People’s decision to don the mask or not, are connected to contesting value orientations.

- Two sides of the mask: When Donald Trump tested positive for Covid-19, Speaker Nancy Pelosi criticised the President for having attended crowded fundraisers and campaign rallies while not wearing a mask: “going into crowds unmasked was a brazen invitation for this to happen”.2 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that “cloth face coverings help prevent people who have COVID-19 from spreading the virus to others.”3 In this light, Trump could be criticised for putting others at risk by not wearing a mask. Pelosi’s remark was interesting because she seemed to think that if Trump had worn a mask, he could have protected himself from the virus. This demonstrates the double meaning of mask-wearing caused by a psychological effect of face covering. From the initial stage of the Covid-19 outbreak, the East Asian practices of public mask-wearing seemed to be driven by individuals’ desire to protect themselves, rather than others. This was widely regarded as unscientific by public health authorities and governments all over the world. When public mask-wearing was introduced in Western nations by spring 2020, people were told to do so to protect others, in case they were asymptomatic carriers of the virus. As soon as one starts wearing them, however, masks give one a sense of protection and safety. More people seem to have started wearing them to protect themselves, rather than others around them. This curious psychological effect of masks, and the transformation in the purpose of their use, needs more critical attention.

Finally, we are left with another question: Will public mask-wearing continue in a post-Covid Western world? The longer the pandemic continues, the more likely it is to become part of Western social norms. However, only time will tell us the answer to this question.

About the Author: Mitsutoshi Horii is Professor at Shumei University in Japan, working at Shumei’s overseas campus in the UK, Chaucer College in Canterbury. His specialisms range from the sociology of risk and uncertainty to the critical examination of the modern Euro-American generic categories in social scientific research. His most recent academic publications include the monograph The Category of ‘Religion’ in Contemporary Japan: Shūkyō and Temple Buddhism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). He is currently writing his forthcoming monograph, The Ideas of Religion and Secularity in Social Theory: A Postcolonial Reflection on Sociology.

References:

1 Burgess, Adam, and Mitsutoshi Horii. “Risk, ritual and health responsibilisation: Japan’s ‘safety blanket’ of surgical face mask‐wearing”. Sociology of Health & Illness 34.8 (2012): 1184-1198.

Horii, Mitsutoshi. “Why Do the Japanese Wear Masks?” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies (2014).

Horii, Mitsutoshi. Masuku to Nihonjin [Masks and the Japanese]. Tokyo: SHI (2012).

3 https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0714-americans-to-wear-masks.html