A mask does not exist in isolation; it presupposes other real or potential masks by its side, masks that might have been chosen in its stead and substituted for it.

-Claude Levi-Strauss, The Way of the Masks

An overwhelming sense of uncertainty fogs the Covid-19 pandemic and cityscapes in India as elsewhere in a planetary reminder of our common environment. Our uncertainties are multi-faceted—personal, practical, and social—but resonate in the insistence that we consider science-based inputs and the accompanying masked and unmasked claims regularly (if not 24/7). As people, cognizing claims that are evolving, we come to inhabit and re-inhabit our masking contexts and practices while embodying the realization that there is no masking our inequities.

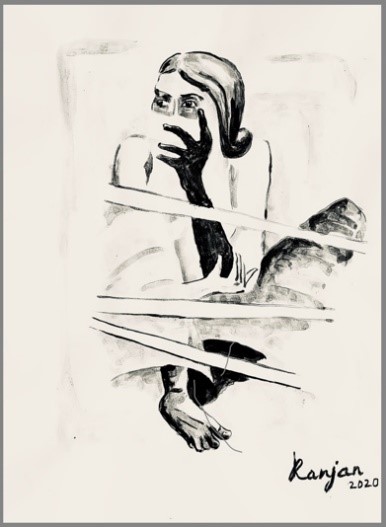

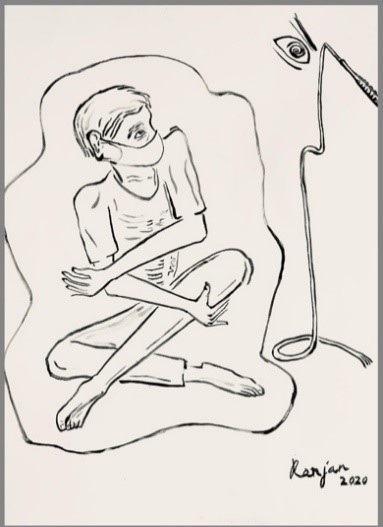

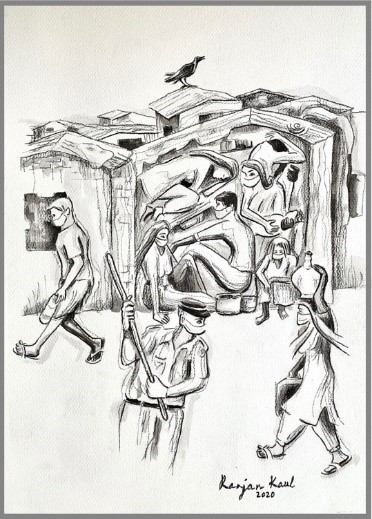

The masked appearance is simultaneously the tell-tale mark of the policed citizen. What lies behind the ubiquitous masking in the city’s underbelly is etched in the accompanying graphic representations. Ranjan Kaul, a Delhi-based artist, portrays the context of slum-dwellers in the city through a panel of charcoal drawings. His first frame focuses on a woman who perceives her hand as unnatural, oversized, and oppressive as it foists a mask that leaves her gagged and bound. The emaciated, masked man in the next frame is immobilized by the state-mandated curfew. The watchful eye and the whip in the corner, ready to be cracked, sums up the ocular display of power outside. The third drawing recreates a condensed image of the slum. People are huddled in a single-room tenement with an ominous crow above. A man is walking back from the slum’s common toilet and a woman is bringing water home (since the area does not have a piped supply). These activities cannot be disallowed, but the image of the policeman brandishing his cane is omnipresent.

“Shut Up” © Ranjan Kaul 2020. Image reproduced with the permission of the artist.

“Whiplash” © Ranjan Kaul 2020. Image reproduced with the permission of the artist.

“Crushed” © Ranjan Kaul 2020. Image reproduced with the permission of the artist.

The artist’s titling accentuates his role as interlocutor, unmasking the perspective of the powerless, but the masking strategies of Delhi’s political honchos and its middle classes also call out for an unveiling.

We see through the masks that our politicians don on mass media in trying to make the nation appear all of a piece, disguising existing inequalities. A mask made of khadi or handloom cloth—fabric symbolic of India’s pre-independence struggle for self-reliance—is the preferred material for making political statements. The charade of such masks is hard to miss—the material is hand-woven cotton, and yet it is a class apart in texture and genre from the loose, coarse cloth that drapes the mouths and noses of the impoverished.

How might one capture the diverse masking moves and strategies of the burgeoning middle classes in the city? Women frequently wear homemade masks or pleat scarfs fashionably and economically while the men, as a class, tend to opt for those that are industrially produced. Washable masks are chosen over the blue-and-white, single-use, disposable surgical masks sold at inflated rates and inhospitable from the angle of environmental recycling and disposal. But without a shred of doubt, no mask is more desirable than the N95 for the middle classes. It is revered as more than a facemask, which presumably filters out 95 percent of suspended air particles. Much before suggestions for reserving it for frontline health workers were articulated, middle-class anxieties had stoked it into becoming the most coveted weapon of self-defense against the virus. It is expensive by average standards, and yet the rush for the N95 gold led it to vanish fairly early from e-commerce sites.

The N95 mask created a flourishing black-market at the chemists. A friend disclosed, “I could get an N95 only after asking a friend, who asked a friend, who asked a doctor, who knew a chemist. Phew!” Another apologetically said, “What mask do I use? I don’t have an N95 but I make do with a black one that I was offered as a substitute.” The N95 has acquired a negative, magical aspect as well. An acquaintance recounted, “I checked with the chemist to make sure that this N95 mask wasn’t from China. Good heavens! I didn’t want anything from there.”

Having managed to procure two or three of the fast-disappearing N95s at exorbitant prices, the betwixt and between people do not rest at that. Figuring out when to wear the N95, for how long, and how to reuse it in an effective, environment-friendly, frugal, and family mode, make up the daily tryst with scientists who said this or that. Most citizens are aware that one-time use of the N95 is considered proper at hospitals. But experimentation is irresistible with the short trip to the grocery store or over that early morning walk. Here the perfect conditions for imperfect figure-it-for-yourself knowledge abound, conjoining science and frugality.

A cousin sanguinely reported that she suns her N-95 mask for thrice the number of hours of use. An acquaintance said, “Ah, the virus dies out after 24 hours max, so I just air it in a clean place for that long.” A friend commented, “Well, at hospitals, the N95 is used for at least four hours at a time. I wash mine in alcohol after 4 hours of use that are spread over four days or so. Hey, but I am not even sure that mine is not a counterfeit N95…just masquerading. I have suspected it all along, but now the papers confirm that the N95s’ branding is something of an uncertified industry.”

At the other extreme, a not-to-be-outsmarted member of the upper-middle stratum proudly declared, “I have an imported N99 mask. I purchased this as an anti-pollution mask from Khan (an upscale market) long before we had a hint of the coronavirus…I wouldn’t buy it now…but it has helped to bring down my anxiety level though you can never be certain. I had purchased three such anti-pollution masks—for my wife, son, and myself—before this corona thing started.” He sent me a picture of the washable N99 mask. It says that it is produced by the “Cambridge Mask Co. England” and “its filters are treated with silver to actively absorb and kill bacteria and viruses.”

Even as the middle strata’s cleaning techniques enact and cloak unknown medical and environmental consequences and risks, the persistent question is how to stretch the N95 and other assorted masks over the uncertain duration of the Covid-19. Caregivers privately express everyday uncertainties about how to keep the uneasiness of masking at bay for the old and the young at home and accompanying transgressions of the scientific temper.

An over-sixty mother was “through with masks that choke” even as her doctor-daughter insisted that masks must be tight-fitting. Another sixtyish mother said that she feared she was “going mental” living alone, and so her son offered to stay with her as he was working from home. As she put it, “Either he or I may be presymptomatic or asymptomatic, but he is flying in to be with me in my tiny flat because… I cannot go on like this much longer…I have cast off my mask.”

A daughter who had not seen her parents over the lockdown period preceded her meeting with a sanitized, brand-new mask. Laughingly she narrated, “Lo and behold! My parents just pulled me towards them and hugged me… their scientific attitude seemed to have evaporated momentarily…” Another youngster conspiratorially declared, “I wear just about any mask to filter out parental worries and as optics for the cops.”

Two of the women I chatted with in my neighorhood had set aside a few homemade masks in their corona-fighting arsenals for a Coro-rainy day. How they came by these masks revealed a story within the story. As the shortage of industrially produced masks exacerbated, it led to a push for homemade masks. In the strike-while-the-iron-is-hot spirit, a few enterprising women here fashioned the mask as an income-generating, ecologically wise stock-in-trade, including designer masks, but did not find sales figures to match. As my young neighbor recounted, without access to thread and couriers through the lockdown, the enterprise could not be strung together for very long. And soon, the produce came to be masked as gifts to friends in the vicinity, sold to neighbors at cost price (to keep tailor salaries going) or offered up as donations.

Perhaps mas(k)querading garbs the uncertainties of our corona times—a mythical dress code in the way of the masks.

About the author:

Rita Brara is affiliated as a sociologist and Senior Research Fellow with the Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi, India. She works on environmental/agrarian law, climate change, gender and kinship, and visual culture. Her most recent research focuses on social constructions of COVID 19, the natural environment and climate change.

This article was first published on Seeing the Woods, a blog by the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society in Munich and is reposted with permission of the RCC and the author.